The last time a Julie Zickefoose book was reviewed on this blogsite, the piece began by saying “This is going to be a rave review.” That sentence will do for this review and this book, too: it’s unavoidable.

Who knew? — but there is apparently an entire literature about women who adopt wild birds and devote substantial portions of their lives and psyches to those birds thereafter, often for years and, necessarily, to the point of obsession. These women, who are all, evidently, sane or close enough to pass, write books, quite good books, about themselves and their charges.

H is for Hawk was a hit for Helen Macdonald a few years back; and Wesley the Owl by Stacey O’Brien, The Parrot Who Owns Me by Joanna Burger; and Alex & Me by Irene Pepperberg are, each of them, delightful books as well.

(And there may be, probably are, men affected with this sort of thing, too, not just women. One thinks, for example, of Robert Stroud, though he had the advantage, or excuse, of being locked in a small cell for life, as the famous Birdman of Alcatraz.)

The latest and delightfullest in this genre is Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard-luck Jay. To readers and to baby birds, its author, Julie Zickefoose, is a treasure.

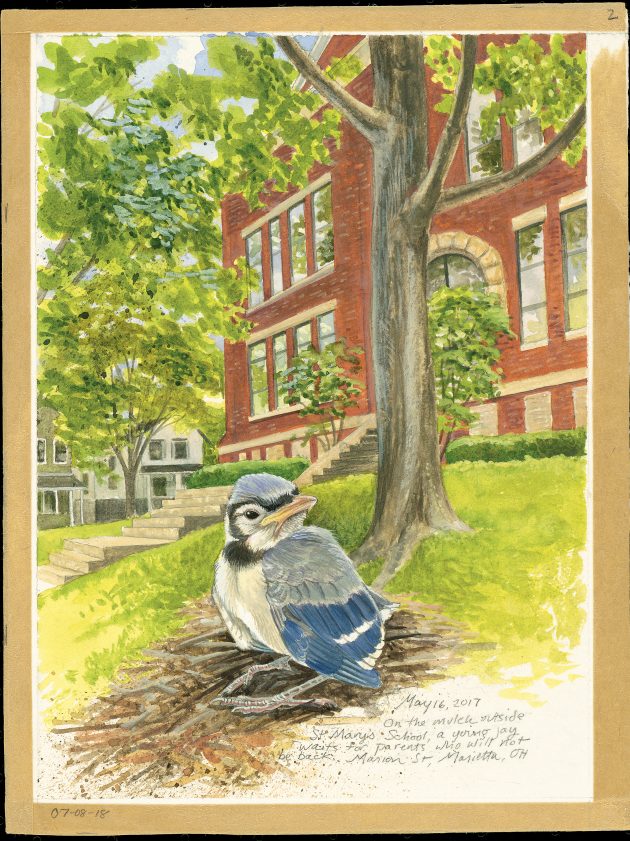

As she has done for many years and with more than twenty species, she adopted a baby bird, a blue jay. Having fallen out of the nest too early, it was sitting in a schoolyard, helpless, hungry and thirsty and sick, waiting for parents who would not be returning. It didn’t have a chance.

Zickefoose made a home for the bird, and nursed it, and immediately became smitten. There was some mayhem involved, poop in the living room being the least part of it. Like all corvids, jays are intensely social beings, and do almost nothing alone. Quickly Julie’s home became “all about the jay.” But she herself had much to do with that: “Almost everything Jemima did made me wonder, chuckle, grin, or gasp, sometimes all at the same time. She was a never-ending source of fascination.”

With a caregiver like Julie Zickefoose, who seems to know everything about baby birds and their physiology (she did, after all, write the book on the subject, the wonderful Baby Birds: An Artist Looks Into the Nest), it would seem inapt to describe Jemima as a “hard-luck” jay, as the subtitle does. But she had one health concern after another. Zickefoose resolutely faced, and solved, every one.

She knew enough, for example, to provide the newborn chick a soft, padded perch: jays are relatively heavy birds, and if they have only hard perching surfaces, they can develop pressure soles on their feet, leading to bumblefoot, a fatal disease.

Later, when Jemima was released into the outdoors, she developed house finch disease, the only cure for which was a 21-day regimen of medicine that had to be Jemima’s sole source of water – and this, while she was already living outside, in the trees. Zickefoose made it happen.

Other problems, Jemima solved herself. She fledged in May; by August she had lost half her primary wing feathers along a “fault bar,” caused, probably, by poor nutrition in the nest. (The losses came from both wings, but the flaw is obvious on the right wing in the photo, below left.)

Her solution: she “flutter-jumped” up through the branches of a tree to the top, from where she could glide at lengths she would not have been able to fly.

And Jemima’s “catastrophic molt,” as Zickefoose says, sounded worse than it was. (It’s a thing that happens to some jays and cardinals: looks weird but the feathers are quickly regrown.) Zickefoose documented the stages of the molt over its eighteen-day course, in her trademark watercolor painting (above right, starting at the bottom and going clockwise).

It’s uncanny (as readers of her previous books already know), how Zickefoose can capture small details and nuance with watercolors. She’s also a fine photographer and a good prose stylist, writing with verve and humor, or scientific precision, or a touching pathos, as appropriate.

“My heart leapt and banged against my breastbone,” she says when, having thought Jemima dead during the winter, she sees a bird in the new year that looks just like her. And, on a less happy occasion, “Cancer settled into our days like the sludge in a jug of cider.”

She drops a hint or two early on, but you wouldn’t really know it until the second half of the book: Zickefoose and her family were undergoing a fair amount of emotional, life-change trauma themselves, of several kinds, during Jemima’s residency. Zickefoose chose, she says, not to focus on loss and regret but on a blue jay; and the book becomes the story of “how saving Jemima saved me.” On a couple of different levels, this is a wonderful story and a terrific book.

Maybe the two photos below could have been taken most anywhere in America – anywhere east of the Rockies, anyway – but once you know that both were taken in southeastern Ohio, you think “yes, of course – couldn’t be anywhere else.” (The pictures show two of Zickefoose’s favorite places near her home, down near Marietta.) Just as is the case with the photos, Saving Jemima is infused with the essence of the place, the eastern Ohio River Valley, once the rim of the North American continent and still a place of wonder and magic.

Saving Jemima: Life and Love with a Hard-Luck Jay

by Julie Zickefoose

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

September 2019, $25

272 pp., 5 1/2/X 8 3/4

ISBN 978-1-328-51895-8

(Photo of Julie and Jemima, above, courtesy of Bill Thompson III; all other photos and drawings courtesy of the author, Julie Zickefoose.)

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Leave a Comment