If you’re out in the woods this spring, trying to see the Woodcock (like that below, left) in the evening, doing his skydance, or trying to entice the Virginia rail (like that below, right) out of the cattails in the morning,

and after a couple of hours you become impatient, bored with your lack of success, and your rear end is wet and cold from sitting on the ground because you forgot your collapsible stool, and the thought that “there’s always tomorrow” is starting to creep into your head, consider this: Donald Kroodsma, the preeminent authority on birdsong, once counted, in one evening, “nearly 21,000” whip-poor-will songs.

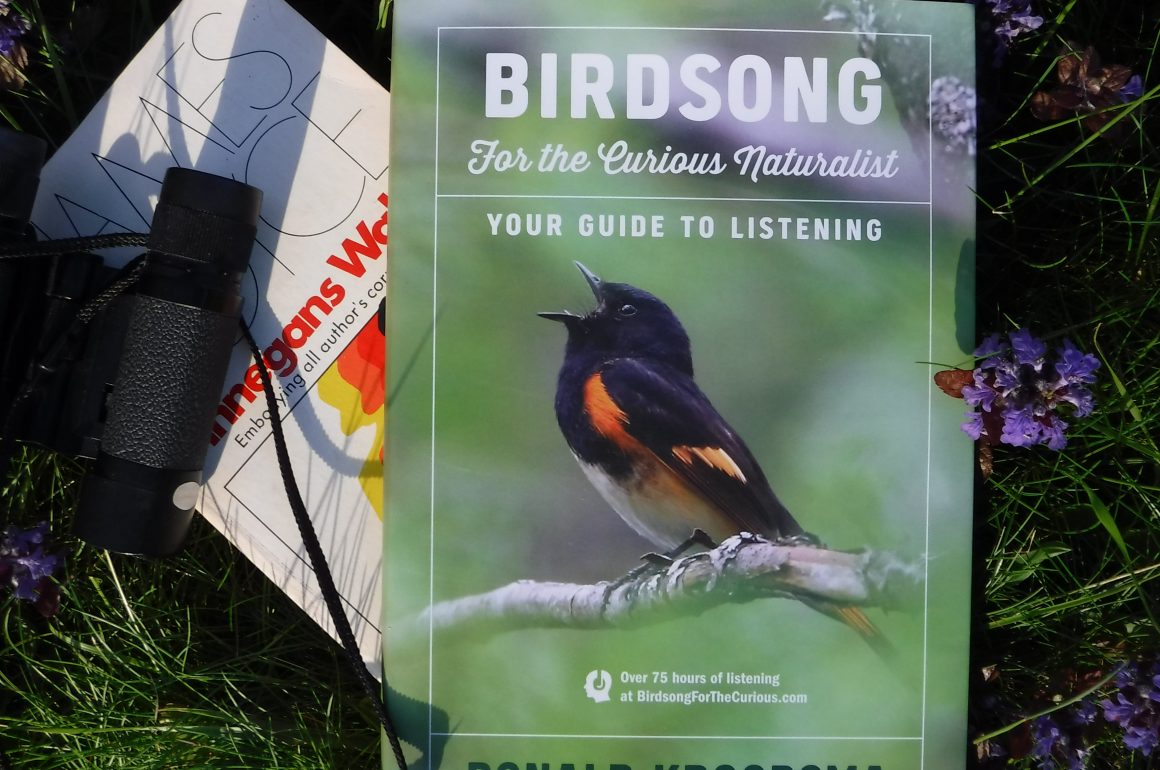

That piece of information, along with many others, comes from Kroodsma’a new book, Birdsong for the Curious Naturalist: Your Guide to Listening — and you have to love the “nearly.” That’s the kind of author you’ll be spending time with – a fellow who has logged fifty years in the field, with inestimable patience, curiosity, and sense of wonder. It’s impossible to think of him being bothered by the wet, cold ground when there’s some count to be made definite after years of thinking about it, some esoteric puzzle to be finally solved.

Like he does, say, for the Canyon wren. Kroodsma waited for years for the right opportunity to record its different songs, a “cascade of sweet and liquid notes,” one naturalist said, “like the spray of a waterfall and sunshine.”

He had long wondered, Kroodsma says, how many songs, exactly, the Canyon wren has in his repertoire. After some hours of recording in northern California, and then, painstaking analysis and listening, he determined the number to be 37, at which point he, palpably exultant, announces to the reader: “a decades-long quest fulfilled.”

In other words, this is a guy who knows everything there is to know about birdsong.

Except he doesn’t!

Not even close. And that’s part of the point of the book, and its charm – how much there is still to be discovered in the realm of birdsong. Over and again, Kroodsma admits to things to which neither he, nor any other researchers, yet have answers – including areas where diligent amateurs can, he says, make discoveries.

He sets the reader up, draws the reader in, to his obsession, with 77 small sections captioned Explore interspersed in the book’s ten chapters – 48 of these “Explores” are in the book, with another 29 on an excellent website that accompanies it. Explore 12 asks about the Wilson’s snipe and its swooping dive, “seemingly intent,” as Kroodsma describes it, “on stitching heaven to earth.” How long does the bird stay aloft, and how many dives does he do? Does he have favorite places to dive? Are the dives coordinated with a neighbor’s? “So many questions,” about this behavior, Kroodsma sighs, “but as yet no answers.”

Other “Explores” are directed at the soft, amorphous practice-singing of young, first-year songbirds (Explore 24, in Chapter 4, “How a Bird Gets Its Song”) and the specific differences between warbler dawn and day songs (Explore 52, in Chapter 7, “When to Sing, and How”). Most of these are the sorts of projects that might be taken on by a weekend birder; others, it must be said, verge on the monomaniacal, such as Explore 32, which involves driving slowly through white-throated sparrow country with the windows open, stopping every 100 miles or so, to understand how and where the eastern “Canada” triplet (as in ohhhh sweet Can-a-da Can-a-da Can-a-da) is being slowly replaced by a western doublet version (as in Cana).

The “Explores” are only part of the book, and there is much else of value in it, even for the reader who cannot quit his job, sell all his worldly possessions, leave his home and family, and take to the byroads armed only with a parabolic microphone. In part, it is a primer on the physiology involved, with a good explanation of how sound is produced in the avian syrinx, with its superfast muscles, “among the fastest twitching muscles known among animals,” Kroodsma says:

The book also includes specific notes on a great number of individual species, with QR barcodes, next to each bird photograph, and some 734 individual recordings. It’s not a field guide, as such. (Good field guides to bird sounds are certainly available, particularly Nathan Pieplow’s for eastern and western North America.) Rather, Kroodsma’s purpose is, he says, for each bird, “trying to fathom who it is, what’s in its head, why in this moment it is singing the way it is.”

This is a wonderful book, unlike any other even you, an avid birder, have on your library shelf — though it’s a good companion to Kroodsma’s previous book, Listening to a Continent Sing. (And, not incidentally, the thing itself is well built, with heavy cover and quality paper.)

The Irishman James Joyce published his novel Finnegans Wake in 1939. It is written in English, mostly, or a form of English anyway, and on first encounter the book and its language is weird, intriguing, puzzling, and beautiful in a way outside the normal realm of experience. But to fully understand it, to be able to “read” it – well, that’s either impossible, or else takes years of dedicated ardor and study. Indeed, all of that was part of Joyce’s purpose and method: he said that the book would “keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant.”

To humans, birdsong is akin to Joycean language, isn’t it? And to follow Kroodsma’s suggested paths, all of them, might take you, not centuries, but surely years. So what? As he says (and he’s absolutely right) once you start listening, you can’t help it: “you will be asking questions, and answering many of them, more and more effortlessly exploring the world of birdsong. It’s a good life!”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Illustrations in this review are taken from Birdsong for the Curious Naturalist. Photographers: Wil Hershberger (American woodcock, Eastern whip-poor-will); Marie Read (Virginia rail, Northern flicker); Robert Royse (Canyon wren, Wilson’s snipe). Drawing of the avian syrinx by Amanda Morgan Riley.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Birdsong for the Curious Naturalist: Your Guide for Listening. By Donald Kroodsma. Harcourt Mifflin Harcourt. Boston, New York. 198 pp., $27, March 10, 2020. ISBN978-1-328-91911-3.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Thanks for this review! I love finding new birding books outside of straight field guides.