I’ve never been to the Indonesian Archipelago, but I really like the birds there. From Great Argus to Coucal to Frogmouth, from Hornbill to Cockatoo to Pitta, from Whistler to Paradise-flycatcher to Jungle-flycatcher to Sunbird (I could go on and on), these are the birds we dream about, the bird names that conjure up fantasies of color and sound amidst jungles, mountain paths, volcanic craters, and magic lakes. Lynx Edicions, the ornithological (and now mammal) publisher that gave us the Handbook of the Birds of the World, has now published Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago: Greater Sundas and Wallacea, by James A. Eaton, Bas van Balen, Nick W. Brickle, and Frank E. Rheindt, a masterful, comprehensive guide to these birds, making it easier for traveling birders to knowledgeably bird the area and harder for homebody fantasy birders to stop drooling over their reading material.

Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago covers 1,417 species, 601 endemics, 98 vagrants, 8 introduced and 18 undescribed species. But, these numbers don’t adequately convey the work that went into this guide, which aims to “present the most up-to-date state of knowledge on the region’s birds for the first time as a whole in a single volume” (Introduction). The archipelago consists of 17,000 islands stretching out over 2500 miles along the Equator with a varied history of avian research and study, most on the under- or not-studied side. The four authors, themselves field ornithologists, conservationists, birders, and writers with years of experience in southeast Asia, researched scientific studies ranging from early 19th-century descriptions of the birds of Java to the latest phylogenomic studies. They studied skins in museums around the world and worked with the artists of Lynx to update the illustrations from Handbook of Birds of the World and to add new ones.

And, then there was the question of taxonomy. Working in an area for which there are few official checklists, no governing taxonomic body, and much new information on species relationships coming in, the authors were faced with a multitude of questions about family sequence, genus arrangements, English common names, and species taxonomy. Co-author Frank E. Rheindt’s section on Taxonomy and Systematics in the Introduction is must reading for birders who are fascinated by taxonomy. Rheindt is an expert on avian phylogenomics and describes both proactive (changing English common names) and unorthodox (“limbo splits”) solutions to these issues.

So, this is no ordinary bird guide. It is a significant achievement, a reference work that presents as a field guide but which also conveys ornithological research from the field, library, and museum and a taxonomy informed by expertise, experience and ingenuity.

Where is the Indonesian Archipelago?

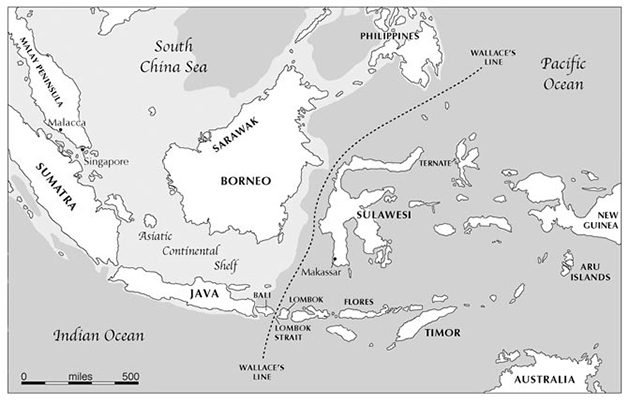

Before we go any further, I think we should talk a little about what constitutes the Indian Archipelago. This area is defined by the authors “biogeographically,” meaning that political borders are irrelevant. The maps on the inside front and back covers help a lot. We’re looking at an area of Asia southeast of the Malay Peninsula and mainland Southeast Asia, southwest of the Philippines, north and northwest of Australia, west of Papua New Guinea (a boundary called “Lydekker’s Line”), intercut by the equator. The two main areas, Greater Sundas and Wallacea, are separated by ‘Wallace’s Line,’ a boundary drawn in 1859 by British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who realized that the two areas had totally different birds and animals. The Greater Sundas area includes Sumatra, Borneo, Brunei, Java, and Bali, and the Wallacea area includes Sulawesi, the Moluccas and the Lesser Sundas plus all satellite islands. So–the book covers islands that belong to the Republic of Indonesia and to Malaysia. But, it doesn’t cover all or Indonesia or all of Malaysia.

Indonesian Archipelago and Wallace’s Line (map from PBS Nova website)

This set me thinking: Do we bird political entities (countries) or biogeographic areas? Does it make a difference? Does the fact that this guide doesn’t include all of Indonesia or Malaysia mean that a birder going to these countries will have to invest in multiple field guides? Experienced travelers know that with weight restrictions being what they are, and the weight and cost of field guides increasing, this can be a problem. But, is it a big enough problem that it should affect the rationale design of a field guide? I don’t have a good answer. If you do, please write it in the comments section.

Other Guides

Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago: Greater Sundas and Wallacea is the first bird guide to fully cover this area. There are two good but outdated guides to parts of the region: A Field Guide to the Birds of Borneo, Sumatra, Java and Bali by John MacKinnon and Karen Phillipps (1993) and A Guide to the Birds of Wallacea: Sulawesi, the Moluccas and Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia by Brian J. Coates, K. David Bishop, and Dana Gardner (1997). There are two excellent guides to the birds of Borneo: Phillipps’ Field Guide to the Birds of Borneo: Sabah, Sarawak, Brunei, and Kalimantan, 3rd Edition, by Quentin Phillipps and Karen Phillips, (2014), and Birds of Borneo: Brunei, Sabah, Sarawak, and Kalimantan by Susan Myers (2009). And, there is A Photographic Guide to the Birds of Indonesia: Second Edition by Morten Strange (2012). I think most birders would agree that the question of political versus biogeographic areas is not as important as rejoicing that we have an up-to-date field guide for the archipelago, period.

Introductory Chapter

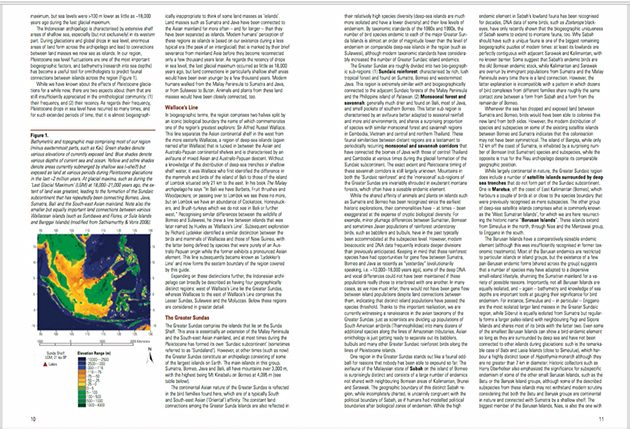

The Earth History and Biogeography section of the Introduction, by Frank E. Rheindt, gives an in-depth education on the geographic history and current state of the region. It concludes with a listing of habitats, which are surprisingly few. But, maybe not when you think about it, since this area was until recently almost totally tropical forest. With the advent of human development, we can now add “farmland and plantations” to various types of forest, rainforest, and swamps. Mangrove areas are disappearing and there are natural areas of savannah in addition to human-created grasslands.

The Introduction also offers sections on Conservation, by Nick W. Brickle, Ornithological History, by Bas van Balen, and the already cited Taxonomy and Systematics by Frank E. Rheindt. The Conservation section is frustratingly brief, stating the expected—massive loss of forest due to logging and a plantation economy, weak enforcement of laws regulating hunting and trade, understaffing of reserves and parks. Only one bird species has become extinct (Javan Lapwing), but many others are endangered, with some considered close to extinction (not surprising in an area with species restricted to one or two small islands). Brickle offers suggestions for supporting conservation in the area, most based on visiting the islands, buying, or not buying, products from companies that have engaged in the worst exploitative practices, and supporting local conservation organizations. These are great ideas, and would be even more effective if the book included a section that listed these local organizations and sources for finding local birding guides and touring companies.

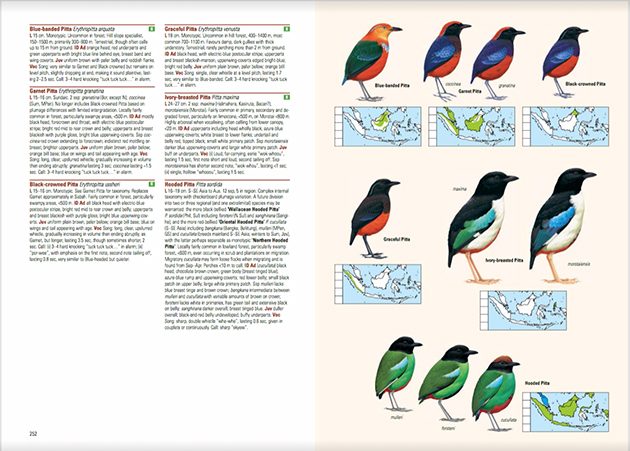

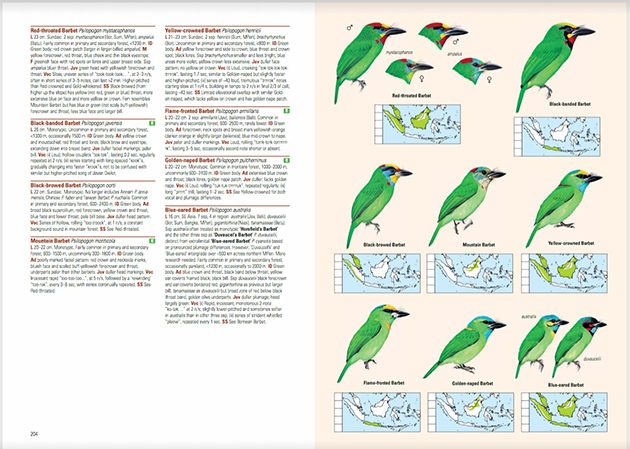

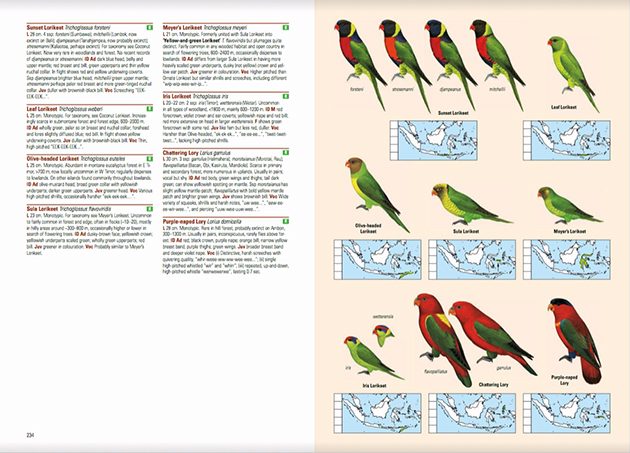

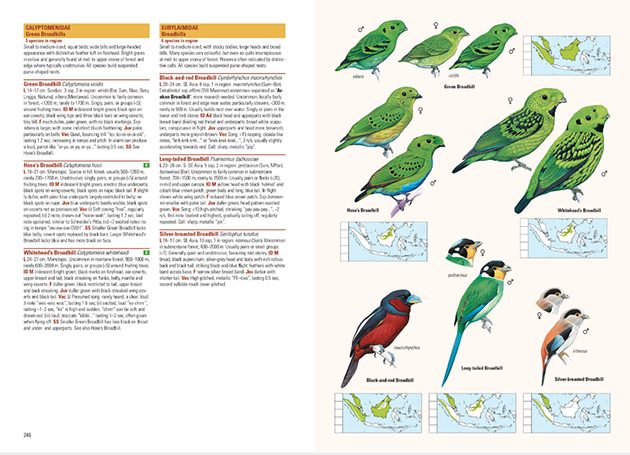

Species Accounts

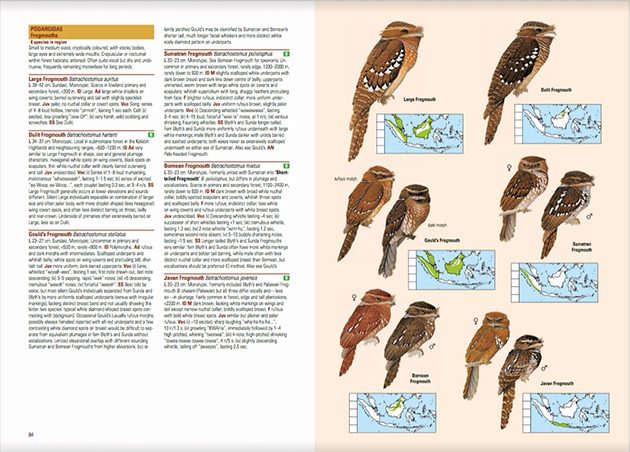

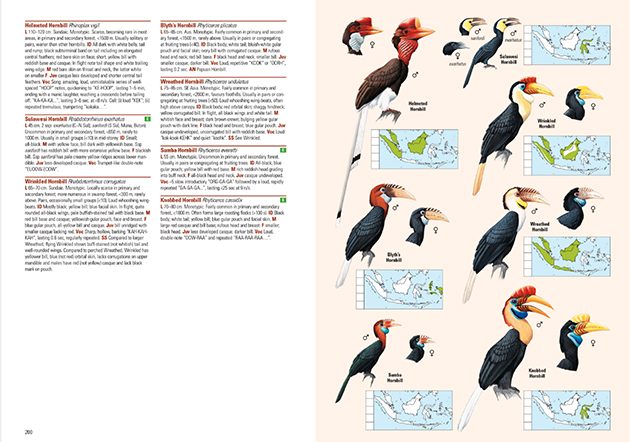

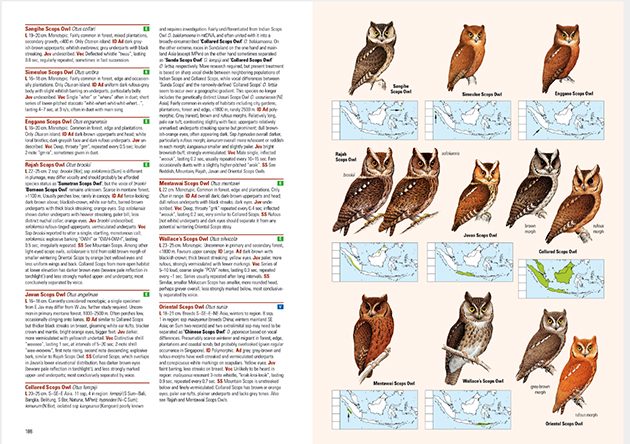

Species accounts are arranged taxonomically, with each family set apart by ochre-colored title boxes, followed by a brief description of the family and how many species are seen in the archipelago. Two-columned text is on the left and illustrations and range maps on the right. Text is brief and compressed, a necessity when dealing with so many birds and you’re trying to keep the total page number under 500. Species accounts are separated by bars, and each category of information is set apart by ochre-colored category titles, abbreviated, which makes finding the exact kind of data you need very easy.

Basic info given for each species: English common name; scientific name; indication (by letter) if the bird is endemic to the region, vagrant, or introduced; size, brief notes on extralimital range for species that occur outside the region; subspecies and geographic range for subspecies in the region; abundance in region and habitat; significant identification features, with an emphasis on adult plumage and notes on juvenile differences; similar species; and alternative names (good to know since the authors have supplanted some traditional common names with updated versions). Many of the accounts include notes on recent taxonomic research, and descriptions of “limbo splits”–possible future splits, which the authors have fleshed out with the assignment of a new English common name, bolded, to go with the scientific subspecies name. Vocalizations are extensively described—song and calls if known—with transcriptions of sound and detailed notes on speed of delivery.

There are more than 1,300 distribution maps, indicating resident birds, breeding visitors, and migrants. The maps are small and arrows are used to indicate the species’ presence on the small islands that make up a good part of the archipelago. The arrangement of the maps with the bird images on each right-hand page are marvels of graphic design; it’s always clear which map belongs to which species, even when the images are not arranged strictly linearly.

Illustrations

The birds illustrated on the right-hand pages are proportional in size; gender and age are illustrated when needed, as are subspecies. Birds are identified in bold print, with subspecies names in italics. The birds are positioned carefully, uniformly facing left or right on each page, for the most part. I like the pages where a new family is shown facing the other way, like page 91, where the nightjars face right and the rails face left. Many, though not all species, are shown in flight (all raptor and shorebird species). Some female and subspecies are depicted partially by head and breast drawings. The text identifying species’ names is bolded, with additional text denoting morphs, adult and immature images, and subspecies names. I do wish the species names were printed larger, but I am glad they are there (as opposed to HBW, where you only get numbers).

More importantly, at least to me, the quality of the art is high. Each image is finely detailed and even look-alike species, such as the Leaf Warblers, are drawn with individual specificity. The colors of the Pittas are deep and jewel-like and the shorebirds are exquisite shades of brown, white, black, gold, and orange. My only problem is the shearwater plate on page 137, where the light undersides are inked so heavily that they appear green. It’s an odd effect, and doesn’t appear on the other seabird plates.

Most of the illustrations are from the Handbook of the Birds of the World, with 105 redrawn and 340 drawn specifically for this guide. This information comes from the January 2017 issue of the HBW Alive Newsletter; aside from a thank you in the Acknowledgements section, there is little information in the book itself on which of the 27 artists listed on the title page are responsible for which sections. The authors give specific nods to illustrators Francesc Jutglar, Juan Varela, and Oriol Massana in the Acknowledgements for their patience in dealing with redrawing requests. I would have liked more, much more, about the illustrative process.

I understand the reasoning behind reusing scientific illustrations owned by the publisher, but I wonder what this means for the future of ornithological illustration. We—birders–have always celebrated bird illustrations as being more than technical drawings. The best illustrations, like those by David Sibley, Guy Tudor, and Sophie Webb are notable for their individuality and artistic aspects. These artists have also traditionally been considered authors or co-authors of their bird guides.

Lynx is taking a different approach. By collecting all the material used in their books in their database HBW Alive– starting with Handbook of the Birds of the World and continuing with bird guides like this one–they are essentially creating a database of avian illustration which they can draw on for future publications. On the one hand this is great, especially if you are a subscriber. The collection will grow and improve, with images of subspecies and gender and age variants being added as new guides are written. On the other hand, since most of the images for new guides will be reused, there is a question of where bird illustrators will find work. I also think it is important that field guide illustrators be recognized and credit given for their work within the publication.

Back of the Book

There are two “back of the book” sections: Selected Bibliography and Index. The excellent 6-page bibliography reflects the extensive scientific literature review done by the guide’s authors–historical surveys, descriptions of new species, phylogenomic studies as recently published as 2015. It includes articles by the authors too, in case you want to read more of their work.

The Index is less satisfactory, listing scientific and common species names (scientific names italicized), and scientific family names (all in caps). The problem is that the English common names are listed in full, alphabetically. So, Chattering Lory is listed alphabetically under “C” and Purple-naped Lory is listed under “P”. But, let’s say I want to see all the Lories. Maybe I’m not sure which Lory I’m observing, or maybe I simply want to study all the Lory species in the region. There is no entry for Lory. And, I’m stuck unless I remember that they are part of the Psittacidae family (not Parrot family, there are no English common name index entries). Or, I can peruse the 107 family listings in the Table of Contents. Or, do a lot of page flipping. In other words, it’s hard to locate the birds unless you know their exact English common name or scientific name or scientific family name. This is a significant organizational problem, especially if you are using the book in the field. If I were to visit the Indonesian Archipelago, I would buy a bag of tabs or a box of post-it notes and spend a lot of time annotating.

Authors

The authors of Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago bring a unique combination of skills and expertise to this project. James A. Eaton is co-founder and guide for Birdtour Asia, a passionate foe of illegal bird markets, and the author of numerous articles about little-known Southeast Asian bird species. Bas van Balen is a freelance ornithologist who has birded and traveled in Indonesia for over 30 years; he is, amongst other things, co-editor of Kukila, the Journal of Indonesian Ornithology. Nick W. Brickle has also lived and worked for many years in Indonesia, is a co-editor of Kukila, and is a co-founder of Burung-Nusantara, the Indian birding and bird conservation website. And, Frank E. Rheindt is a former bird guide and current professor at the National University of Singapore; he has written extensively on Southeast Asian birds and avian phylogenomics, and he is a member of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.

Conclusion

Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago: Greater Sundas and Wallacea is the bird guide you will be using if you plan to bird these exotic and, in many cases, isolated islands. Its comprehensive text, steeped in the latest ornithological scholarship, its distribution maps, pinpointing the tiniest island, and its highly detailed, colorful illustrations are the guide’s strengths. Organizationally, the guide can be challenging to use, and the addition of tabs and/or annotations is suggested. Overall, this guide is a significant addition to our body of birding literature, and may even encourage more American birders to visit the Indonesian Archipelago.

Although Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago is called a field guide by the authors, it is a little too big and too heavy to be used easily in the field (at this point, only a hard covered edition is available). It is perfect for the car, and maybe even for the packs of strong-backed birders. This is also a very expensive book, costing $75 to $85 from online booksellers without the usual Amazon discounts. But, let’s face it, if you are traveling to the Indonesian Archipelago, spending a little more for the best and only bird guide on the whole area is part of the cost of travel. You get a lot of info for the dollar and you get the images of those incredible, beautiful birds. Fireback, Needletail, Boobok, White-eye, Broadbill, Flowerpecker–for some of us, that’s the next best thing to being there.

Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago: Greater Sundas and Wallacea

by James A. Eaton, Bas van Balen, Nick W. Brickle, & Frank E. Rheindt

Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, November 2016, 496 p.

ISBN-10: 8494189263; ISBN-13: 978-84-941892-6-5

Format: 6.3 x 1.2 x 9.1 inches, Hardcover

More than 2,500 illustrations and more than 1,300 distribution maps.

Price: 65.00€ direct from Lynx; $75 to $85 from other online nature booksellers.

Thank you to Lynx Edicions for providing a review copy.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Wow, what a fantastic addition to the library that would be!

Took this book to Indonesia recently. It is too heavy and the alphabetical indexing is bewildering. Obviously not developed by a watcher of birds as a genuine field guide.

I usually get these “monsters” rebound with a soft cover and only plates and alpha index included for convenience when travelling. Layout of this book makes that approach prohibitive.

So, next best option is a print in soft cover with redeveloped alphabetical species list.

Great review. I’m an American birder currently living in Indonesia and I use this book all the time. I found an index/table of contents on the internet. I printed it and pasted it into the front of the book. It helps solve the strange indexing issue. Does anyone know why all the range maps have those 5 boxes on the left side? Are they latitude lines?