Happy New Year, 10,000 Birds readers! For my first post of 2021, I’m going to reach back to a review originally published six years ago. I remember how awestruck I felt while I was reviewing Birds and People, I was so excited that I was going to write about this book so full of images and knowledge. And, over the years I have used Birds and People extensively, both as a resource when reviewing other books and for my own pleasure and education. So, here’s a look again at a special book, a most appropriate title for a time when so many people are discovering birding.

—————-

It took me a while to wrap my mind around the concept of Birds and People, Mark Cocker and David Tipling’s book that, in 592 pages, explores the intersection of just that—birds and us. I’m not sure why. It’s not like I had forgotten lists created with friends of ‘songs with birds in the lyrics’, my personal favorites being Sondheim’s Green Finch and Linnet Bird and the Beatles’ Blackbird. Nor have I overlooked “sightings” of birds in movies mouthing other birds’ calls. I’ve frequently paused in front of wine bottles with birds on their labels, wondering if this is a sign of a good vintage. And, I’ve passed through the Ancient Egypt exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum, where the Ibis is featured on pottery fragments, many times.

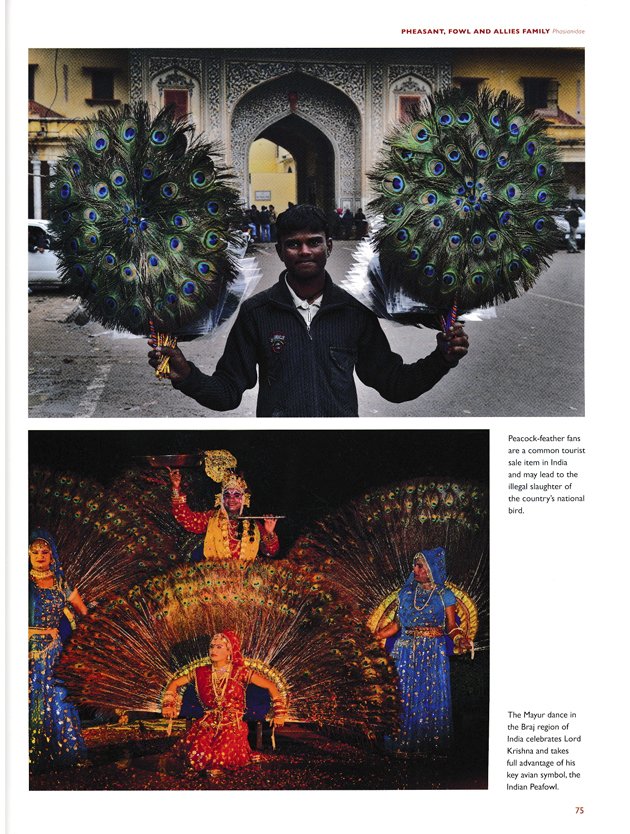

Still, I found it a little disjointing that a book has been written about our relationship with birds. Perhaps it comes from keeping a conscious distance while I observe them. As I explained to my nephews when they were younger, “The Burrowing Owls don’t think we’re their friends. People on one side of the rope, owls on the other.” (Substitute Snowy Owl here if you’d like the modern version). Perhaps it’s because the topic is so huge, it’s difficult to comprehend in a systematic way. It’s relatively easy to classify birds into family groups based on physical characteristics. It’s very hard to organize the many ways in which human beings relate to avian beings into comprehensible text. We sing about them, we paint them, we use them as mythic and poetic symbols for our spiritual and emotional feelings, we wear them in myriad and often colorful ways, we adopt them as household pets. We view them as our enemies when they eat our crops and as an extension of our family when we see them at our feeders. We worship birds, we hunt birds, we protect birds, and, yes, we eat birds. As they say, the relationship is complicated. So, I just sit here, amazed at this book. I love reading it, but I also I find it hard to focus at times because I can’t help thinking about the thousands of hours Mark Cocker put into creating this unique volume. A British author and naturalist, Cocker has authored nine books, remarkable for their breadth of subject—biography, history, memoir, and literary criticism. He started working on Birds and People in January 2007, according to the book’s web site, and the project ultimately took six years. David Tipling, award-winning and widely published wildlife photographer, travelled the world during this period, photographing people interacting with birds, and sometimes, just birds. Jonathan Elphick and John Fanshawe provided “specialist research” and support.” The project is co-sponsored by BirdLife International, the international conservation consortium that has been initiating partnerships with artists and writers that celebrate birds.

So, I just sit here, amazed at this book. I love reading it, but I also I find it hard to focus at times because I can’t help thinking about the thousands of hours Mark Cocker put into creating this unique volume. A British author and naturalist, Cocker has authored nine books, remarkable for their breadth of subject—biography, history, memoir, and literary criticism. He started working on Birds and People in January 2007, according to the book’s web site, and the project ultimately took six years. David Tipling, award-winning and widely published wildlife photographer, travelled the world during this period, photographing people interacting with birds, and sometimes, just birds. Jonathan Elphick and John Fanshawe provided “specialist research” and support.” The project is co-sponsored by BirdLife International, the international conservation consortium that has been initiating partnerships with artists and writers that celebrate birds.

The book is divided into 143 chapters covering 144 bird families and 2 extinct families, plus an ending chapter on Birds, People, and Birdlife International by its president, John Fanshawe. Remarkably, there are 59 bird families that have very little cultural significance; these are listed in Appendix III. Additional back of the book material includes a Glossary, Biographical Details, a Select Bibliography, Notes, Credits, an Index to Species and a General Index.

The chapters themselves are full of surprising facts and stories, densely packed. Cocker writes about the species within each family with a literary specificity softened by a tone of conversational patience. Reading each chapter is like listening to a very knowledgeable friend hold forth on esoteric topics you didn’t think you cared about but ultimately find accessible and fascinating. He often goes quickly through the material, but there are times when he expands on a subject about which you sense he feels very deeply. Larks, for example. Cocker presents Eurasian Larks as a prime example of one of the recurring themes of the book, our culture’s tendency to cherish a bird in poetry and myth and to simultaneously exploit, even ravish, the actual bird. He describes lark mirrors and other contraptions that were used to entice the birds into traps in detail, and cites the few documented numbers of larks sold in market in the early 19th century (826, 462 in the Paris market in 1832). This comes after a long section on the celebration of skylark song in poetry and religion, a source of “divine grace” or, as in Shelley’s To a Skylark, a metaphor for the creation of poetry. The irony, Cocker writes, reflects both an overall environmental issue and a personal sense of loss.

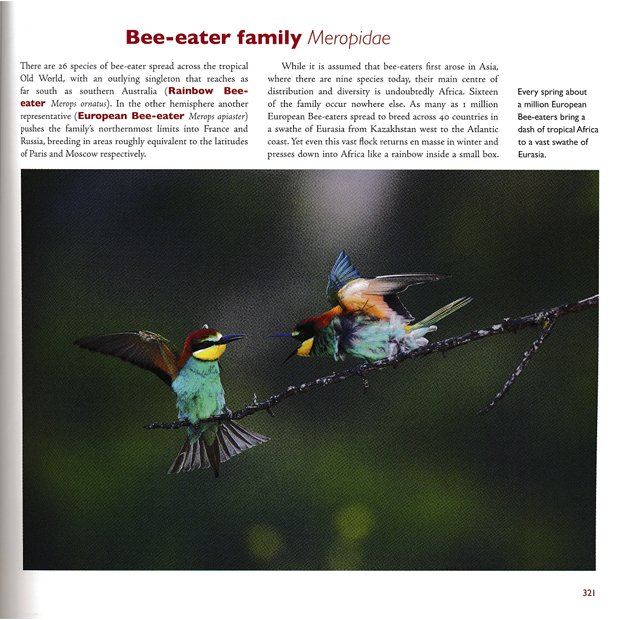

I was surprised at how much and how little cultural significance different bird families hold for us. The beautiful Bee-eater family, with its 26 species, is covered in a little less than two pages. Cocker talks about Aristotle’s surprising accurate knowledge of Bee-eater behavior, their contentious relationship with apiarists, their association by early Hindus with gods of marksmanship (their flight shape resembled bows and their aim while chasing insects reminded them of arrows), and the beauty of their colonial nesting sites.

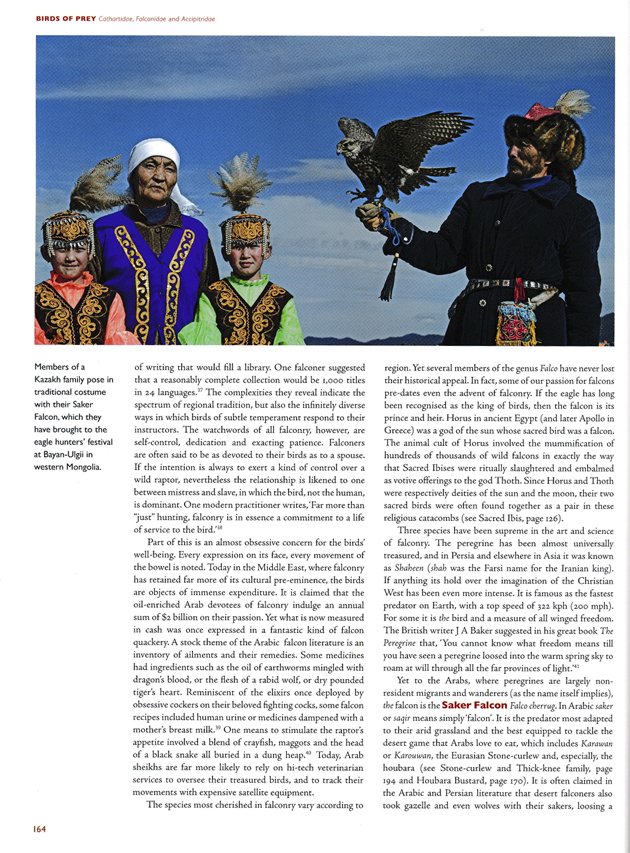

The Birds of Prey chapter, on the other hand, is 18 pages long. It includes stunning photographs by Tipling of eagle hunters (as in Kazakhs who hunt with eagles), Stellar Sea Eagles in Hokkaido, Japan, and Black Kites at the dump near New Delhi, India. Cocker focuses on the love-hate relationship we have with raptors. Eagles are national symbols of the U.S., and also Modern Iraq, Egypt, Albania, Mexico, Poland and the Philippines. We politically worship them, but at the same time we’ve severely decreased the numbers of many species by hunting and habitat loss. Cocker paints this in a personal light, writing, “The same people who cherish the symbol can still despise the living bird.” He delights in falconry, still actively practiced in the Middle East, describing its history and rites, and noting that “…the relationship is likened to one between mistress and slave, in which the bird, not the human, is dominant.”

One of the more interesting aspects of Birds and People is its use of stories by just plain people. Cocker put out a call for people’s personal experiences with birds and people responded, over 600 people, most of who are credited in the Acknowledgements section. About 300 stories are used throughout the book. They range from feelings on hearing a Pied Butcherbird sing to an eyewitness account of the Yawar Fiesta, in which an Andean Condor fights a bull, to a Kenyan’s problem with Mousebirds in his garden. The universality of people’s love of thrushes in their gardens is illustrated by three stories from people living in Kenya (Olive Thrush), Canada (American Robin), and England (Common Blackbird).

I found this use of ‘regular people’s’ stories initially disjointing; it threw my librarian concept of a reference book out of whack. Reference books are supposed to be full of documentable facts, not stories from people without a PhD next to their name. But, this is not a reference book in the classic sense. It is a book that aims to make us conscious of our historical and daily connections to birds in all parts of our life. And, that just isn’t documented in scientific papers. By including these stories, Cocker has created a book that is very much a part of our current information age, in which democracy rules. Think of Wikipedia, the encyclopedia created by the masses, and Kickstarter, in which anyone can contribute to funding for a creative project. The 300 stories enhance the thousands, maybe millions of facts Cocker has compiled, creating a volume that speaks to a collective human experience that is rooted in both poetry and science. A few words about the back of the book material. I was really happy to see that there are two indexes. The Species Index consists of common bird names, with pages of illustrations italicized. The General Index lists names, places, subdivided by species, and a few activities (talking birds, fortune telling), and concept (symbolism) and titles of songs and films. I really would have liked to have index entries by cultural activity–general headings for songs, films, art, etc. But, in an age in which most reference-type books have very limited indices, I am delighted that the authors included this index, which I’m sure will be very helpful to readers and students.

A few words about the back of the book material. I was really happy to see that there are two indexes. The Species Index consists of common bird names, with pages of illustrations italicized. The General Index lists names, places, subdivided by species, and a few activities (talking birds, fortune telling), and concept (symbolism) and titles of songs and films. I really would have liked to have index entries by cultural activity–general headings for songs, films, art, etc. But, in an age in which most reference-type books have very limited indices, I am delighted that the authors included this index, which I’m sure will be very helpful to readers and students.

The inclusion of Biographical Details of ornithologists cited regularly in the book (Arthur Bent, Aldo Leopold, Pliny the Elder, are three examples) is another nice feature. The Select Bibliography, 13 pages of books and articles consulted and researched, is excellent but limited in that it does not include online references. Notes is where you go to look up the footnotes in the text documenting every fact. As one of those people who likes to look these things up as I read, I found it a little difficult to use because of the lack of page numbers next to each chapter title. Surprisingly, there are occasional references to web sites in this section. Overall, these remarks should not take away from the general excellence of the back of the book material, which reflects a high consciousness of the scholarly need for documentation and also the possibility that readers might want to pursue some of these subjects on their own.

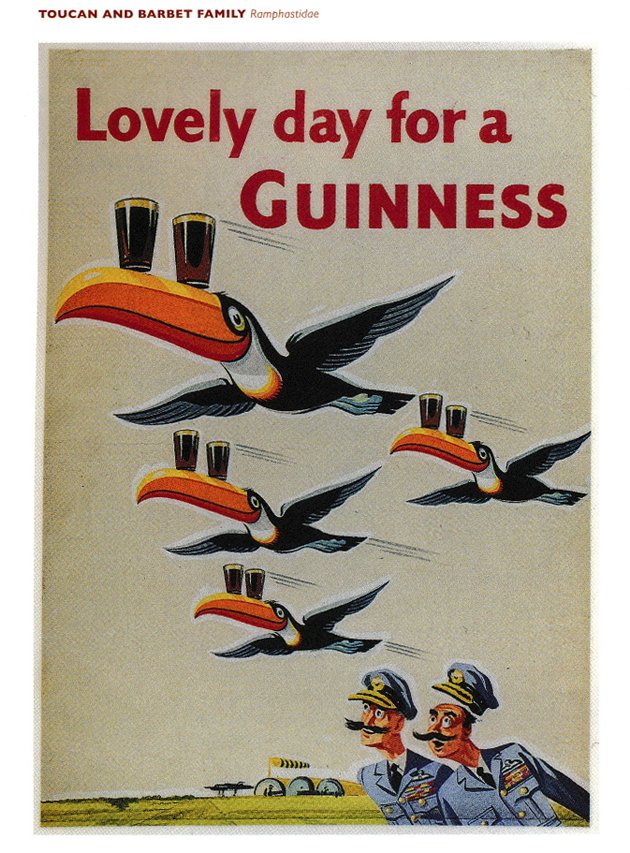

Birds and People is an exceptional book. It is a large, heavy book, and reading it might present a challenge to those of us who like to balance books on our knees as we recline on the couch. It is also a relatively expensive book. But, it is a book that every birder who wants to know more about birds than what they read in a field guide will want in her or his library. It provides a context for our passion. I don’t think a month goes by when a non-birder friend asks me “Why are you a birder?” Well, after reading Birds and People, I’ll be able to reply, “How can I not be a birder? Think about their image. Birds are all over, on our advertisements, on the opening to the Colbert show, on the wall of the Frick Museum, in our yards, on our dinner plates, in our collective history.” (Let me note now that the Colbert show opening is not cited in the book, nor is Carel Fabritius’s 1654 painting, The Goldfinch, though there is a section on The Place of the Goldfinch in Renaissance Art. Cocker just could not include everything. Which opens the door for each of us to make our own personal Birds and People lists!)

This is also a book that provides a wealth of material for why we need to make conservation a core part of our lives as birders and in the larger sense, as a culture. As Cocker writes in the Introduction, “It is only when whole societies collectively believe in the goal that it is attainable.” What would a world be without birds? We would be bereft of food, yes, but we would also be without a spiritual core. Birds and People, a book of stories and facts and opinion, makes clear that this is not an option.

—————————————-

Birds & People

By Mark Cocker (author) and David Tipling (photographer)

Random House UK, September 2013. $65.00.

592 pages (Amazon says 704, but this is incorrect), 11.3 x 8.9 x 1.8 inches, 5.9 pounds (shipping weight)

ISBN-10: 0224081748

ISBN-13: 978-0224081740

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

I’ve seen images of this book cover so many times online (thanks, Google algorithms!), but had no idea it was such an expansive and comprehensive volume. I’ll have to try to get a copy one of these days.

You can tell that this was originally written several years ago, because Donna says “I’ve frequently paused in front of wine bottles with birds on their labels, wondering if this is a sign of a good vintage.”

If this was a new post that thought would be completed with “… so I asked Tristan.” 😉

“falconry, still actively practiced … and noting that “…the relationship is likened to one between mistress and slave, in which the bird, not the human, is dominant.”

Oh how strongly I disagree here! Those birds are so manipulated that they are mentally ill, not even knowing that they are birds and trying to mate with falconers!

“One of the more interesting aspects of Birds and People is its use of stories by just plain people… , most of who are credited in the Acknowledgements section.”

I am one of those credited, though, not for any significant contribution.