Birders know that some of the finest birding locations in the country are on federal land, which include national parks, wildlife refuges, forests, monuments, and seashores, among others. These lands support countless birds, either year-round, as migratory stopovers, or as breeding grounds. But what else should birders know?

There are Vast Amounts of Federal Land

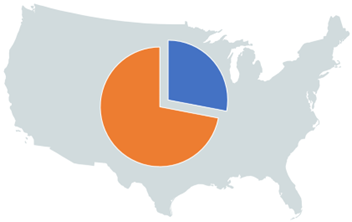

Approximately 28% of the entire land area of the United States is federal land, about 640 million acres. However, federal land is not evenly distributed within the United States.

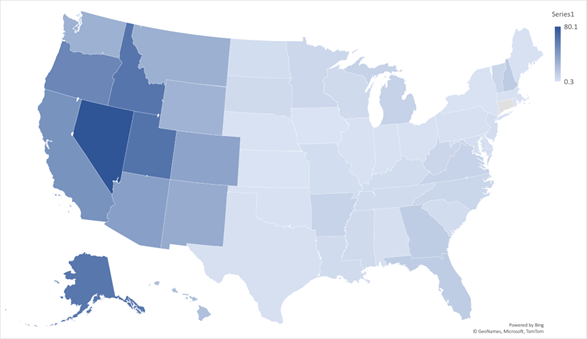

On a state-by-state basis, that percentage increases dramatically as one moves from east to west. In fact, the overwhelming majority of federal land is in just 11 western states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming). The federal government owns about 46% of the land in these states but only about 4% of the other states (excluding Alaska). For example, the federal government owns less than 1% in Connecticut but nearly 80% in Nevada.

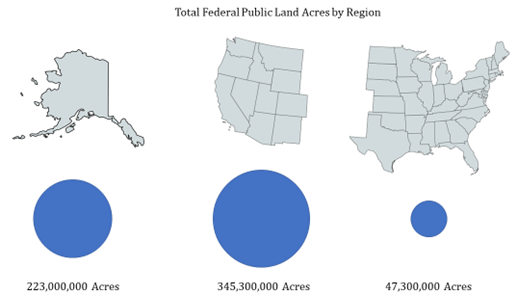

There is one gigantic outlier: Alaska. The federal government owns roughly 223 million acres in Alaska, about 61% of the state. The four largest national parks are all in Alaska, including the largest, Wrangell-Saint Elias NP (more than 8.3 million acres). The eleven largest national wildlife refuges are also in Alaska, including Arctic NWR and Yukon Delta NWR, each more than 19 million acres. In terms of federal land, Alaska truly stands apart. In fact, approximately 36% of all federal land is in Alaska.

Thus, federal land is concentrated in the west and, on a truly enormous scale, in Alaska.

Federal Land Managers: Different Agencies, Different Missions

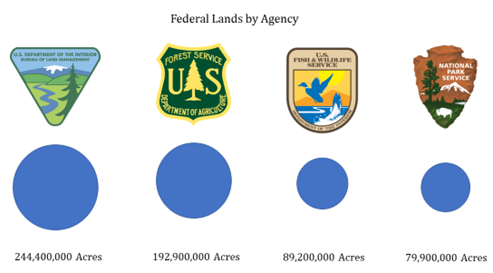

The federal government manages its lands through an alphabet soup list of agencies, but the overwhelming majority is managed by four agencies:

- Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

- Forest Service (FS)

- Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)

- National Park Service (NPS)

BLM, FWS, and NPS are part of the Department of the Interior, while FS is part of the Department of Agriculture. Additionally, the Department of Defense administers about 9 million acres, primarily military bases and training ranges. A variety of other agencies own the remainder.

- Bureau of Land Management: BLM is the largest federal landholder and virtually all of its holdings are in the west: 99% is in the 11 western states and Alaska. BLM’s mission is one of multiple-uses and sustained yields, such that it attempts to balance energy development, grazing, recreation, and timber harvesting, while simultaneously attempting to preserve natural resources. Much of the BLM’s land is rangeland, and it is often leased for grazing or energy development. BLM land is particularly important for conservation of the Greater Sage-Grouse and other sageland species.

- Forest Service: The Forest Service manages 154 national forests and 20 national grasslands, also under a multiple use concept, meaning they are managed to provide a number of services, including lumber, grazing, minerals, and recreation. A broad array of birds make use of FS lands, including warblers, flycatchers, thrushes, and many others.

- Fish and Wildlife Service: The stylized blue goose logo of the FWS is well-known to birders, as FWS manages more than 575 national wildlife refuges. FWS is unique because its primary statutory mission is conservation. Other activities, primarily wildlife-related activities such as wildlife observation, photography, and education, are permitted only when consistent with the primary conservation goal. Although FWS manages a diverse portfolio of lands, many refuges were created for waterfowl conservation.

- National Park Service: Perhaps the most familiar large federal landowner, NPS manages national parks, monuments, seashores, and other areas of cultural and historical significance. NPS attempts to balance multiple uses, including enjoyment by the public and natural resource conservation. Conflicts have been inevitable and there have been concerns, particularly at the most popular national parks, that we are “loving our parks to death.” NPS also manages a diverse set of lands (i.e., from the Arctic to the Everglades to the Mojave Desert to the Rocky Mountains) that are used by many species of birds.

Thus, federal land is primarily managed by four agencies, most of which attempt to balance multiple goals, only one of which is conservation. Only FWS has the primary goal of conservation.

Federal Lands are Vital to Birds

Federal lands are vast and diverse, from the far north (Arctic NWR in Alaska) to the Caribbean (Virgin Islands NP in the U.S. Virgin Islands). They stretch from the middle of the Pacific Ocean (Midway Atoll NWR in Hawaii) in the west to the Atlantic coast (Acadia NP in Maine) in the east.

The birds that rely on federal lands therefore include virtually every species that spends meaningful time in the United States. Nonetheless, some birds make disproportionate use of federal land.

For example, migratory waterfowl make extensive use of national wildlife refuges during migration or as wintering grounds. Indeed, many refuges were created specifically for migratory waterfowl and are managed for their benefit. Many refuges are strategically located along major flyways, allowing ducks and geese to hopscotch their way up the continent to northern breeding grounds and back down again. Numerous refuges are known to birders for their enormous numbers of wintering waterfowl.

Perhaps surprisingly, federal lands are critical for many seabirds. The most significant breeding areas in the country are isolated islands in the National Wildlife Refuge and National Park Systems. These include: Hawaiian Islands NWR, Farallon Islands NWR near San Francisco, Alaska Maritime NWR, and Channel Islands NP near Santa Barbara. For example, most of the world’s Black-footed and Laysan Albatross and Ashy Storm-Petrel breed on these islands.

Several endangered species are (or have been) highly dependent on specific tracts of federal land. For example, Whooping Cranes winter almost exclusively at Aransas NWR in Texas. The Laysan Duck is found on only two remote Hawaiian atolls, both NWRs. Spotted Owls depend on old growth forests, largely in national forests and parks in the Pacific Northwest. California Condors rely on Pinnacles, Grand Canyon, and Zion national parks, as well as Bitter Creek and Hopper Mountain NWRs. For decades before the reintroduction of additional populations, the Puerto Rican Parrot was only found in El Yunque NF near San Juan.

Conservation Laws are Particularly Strong on Federal Lands

Although laws such as the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act apply to both public and private actors, they generally apply with greatest force to federal agencies, including those that manage federal lands. Thus, legal protections for endangered species and conservation generally are at their zenith on federal lands.

This includes the military. For example, several bases in the Southeast—Camp Lejeune, Fort Bragg, Fort Benning, and Eglin Air Force Base—have long been managed to support large populations of Red-Cockaded Woodpeckers.

As a result of the amount and location of federal lands and these legal projections, studies have indicated that federal land is much better for imperiled species than private land. In particular, federal lands lose far less habitat than private lands, making them much better for wildlife.

Additionally, many federal lands have further protections. In areas designated “wilderness” under the Wilderness Act, commercial activities, roads, and structures are prohibited, as are cars, trucks, and off-road vehicles. Accordingly, the more than 100 million acres designated as wilderness are some of the most protected lands in the United States. Additionally, the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System preserves more than 13,000 miles of rivers in a free-flowing condition.

Photo: Trunk Bay, Virgin Islands NP.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Very timely post as I am about to go birding on federal land in Colorado…

Really appreciate this type of article, Jason, and the information / perspective it provides.

Thank you.

I really appreciate the work you put in on this blog. It was well put together and informative. The pictures were awesome. Beautiful birds and beautiful flowers are something I have always enjoyed. I used to raise endangered species of pheasants currosals and quail. Again thank you for this website