How much do you know about owls? This isn’t a rhetorical question, think about it. I’ve been fortunate to encounter many owls in my birding life, sometimes because I’m looking for them, sometimes happily by happenstance. I’ve observed nesting owls, fledgling owlets, owls eating small rodents, owls coughing up their pellets, a Great Horned Owl silently flying over me, a Great Gray Owl sitting regally still on a post as a boy walks up to him, a pair of Barking Owls duetting in early evening hours outside my northern Australian hut as I brushed my teeth. I’m sure many of you have had similar experiences. But what do we know beyond these commonly seen and heard behaviors? And how much do we know about why and how they behave this way? Jennifer Ackerman points out in the introduction to What the Owl Knows: The New Science of the World’s Most Enigmatic Birds, that we don’t know much, but that very soon we may know a lot more.

Ackerman’s new book is about owls and owl research–the knowledge recently and currently being discovered through DNA analysis, new-tech tracking and monitoring, and old-fashioned fieldwork under the auspices of organizations like the Global Owl Project and the Owl Research Institute. It’s also about human-owl interaction on an individual level and a wider sociocultural level, and ultimately how we can use all this for habitat and bird conservation. I’m wondering as I write if you are shaking your head, uneasy that all these FACTS will interfere with your love of observing owls, an experience that easily borders on the mystical for some of us. I don’t think so. Jennifer Ackerman brings a sense of curiosity and wonder to her material, whether she’s interviewing evolutionary ecologist Christopher Clark about the mechanics of an owl’s silent flight or looking for Northern Pygmy Owl nests in Montana with a team from the Owl Research Institute. She excels at bringing together complicated strands of a scientific question and its answers, but is first and last a storyteller. What the Owl Knows: The New Science of the World’s Most Enigmatic Birds is a joyous, fascinating read.

© 2023, Jennifer Ackerman; page 14 photograph “courtesy of Ambika Angela Bone”; page 15 photograph “courtesy of Matt Poole.”

© 2023, Jennifer Ackerman; page 14 photograph “courtesy of Ambika Angela Bone”; page 15 photograph “courtesy of Matt Poole.”

Writing about owls means writing about roughly 250 species (I counted 245 on the 2022 Clements spreadsheet, but I might have missed a few, and we all know that each classification system is different). The species are taxonomically divided into two families: Tytonidae, Barn-Owls, and Strigidae, Owls, encompassed in one order, Strigiformes. When you look at Clements latest taxonomic spreadsheet, you get a sense of the depth of their relationships to each other and the world. Owls live and migrate from Arctic circumpolar to Colorado prairie to South American rainforest to Southeast Asian islands, Galapagos islands, Canary islands–many many islands–to coastal Australia and onward. Their common names reflect their size, appearance, residence, and sometimes their sound, ranging from the simple to the eponymous: Little Owl, Powerful Owl, Pharaoh Eagle-Owl, Cloud-Forest Pygmy-Owl, Pearl-spotted Owlet, Morepork, Christmas Island Boobook, Blakiston’s Fish-Owl. Owl numbers and names expand when you look at subspecies: at least 29 Barn Owl subspecies, 16 Burrowing Owl subspecies, 13 Little Owl subspecies, to name the most outstanding. As the names and habitats imply, not all owl species are alike, in behavior, adaptation, relationship to humans, and in how humans perceive them. The range of differences is partly what makes this book so captivating, and also must have been both challenging and intriguing to Ackerman.

What the Owl Knows is organized into nine chapters: introduction, adaptation (including vision and flight), research and researchers, vocalization, courtship and breeding, roosting and migration, cognition, and two chapters on owls and humans–captive owls (not zoos, educational owls) and owls in our cultural history. There is also an afterward on conservation, though it’s not clear why this isn’t a tenth chapter. The chapters on courtship and breeding and roosting and migration are the longest, which isn’t surprising. These are behaviors that are most likely to vary across species and topics that make for compelling stories. But there really isn’t a chapter that doesn’t offer a good story. Ackerman understands how to set a scene, fill it with charismatic real-life characters, and top it off with magic–the hoot of a distant Great Gray Owl, a Burrowing Owl evading capture, an old barn sheltering young Barn Owls, a tree full of Long-eared Owls in the middle of a small town in northern Serbia.

Two figures that show up in almost every chapter are David Johnson, director of the Global Owl Project, and Derek Holt, founder and president of the Owl Research Institute, both of whom are involved in so many projects you wonder if they’ve mastered the art of slowing down time. Johnson is collecting myths about owls from cultures around the world and is also presiding over a 12-year Burrowing Owl Project that seeks to collect DNA samples, vocalizations, morphological data and map locations for every Burrowing Owl subspecies the world over. Holt and his staff, several of which are also ‘characters’ in the book, do hard-core field work, finding owls, owl nests, documenting them and working with concerned and unconcerned organizations to inform public policy decision-making. Holt also travels up to Utqiavik, Alaska every June, and has been for over 30 years, to study Snowy Owls and Brown Lemmings. There’s also people like Steve Hiro, a retired heart surgeon who volunteers with ORI and has focused on studying the Northern Pygmy Owl; Marjorn Savelsberg, a talented musician who had to give up a professional career when she developed heart disease and who now spends her nights recording Eurasian Eagle Owls in a quarry in the Netherlands; and Gail Buhl of the Raptor Center at the University of Minnesota, who trains rehabilitated captive owls.

“Well, that’s great,” you may be saying, “but what does that have to do with owls? I want to read about owls, not people.” It is all about the owls. From Holt we learn, amongst many things, his theory about why adult male Snowy Owls are white (hint, it’s about what the female Snowy Owl thinks). From Hiro, we learn how Northern Pygmy Owls are “rule breakers,” not incubating eggs till all are hatched and then raising owlets that mature at the same rate even though the eggs were laid asynchronously (as most owl eggs are). From Savelsberg, we get insight into the mating behavior of Eurasian Eagle Owls, toppling set ideas about owl monogamy; her work has also laid the groundwork for using auditory technology and analysis for other owl studies. From Gail Buhl, we get a point-by-point speech on owl behavior, including how to recognize if an owl is disturbed and afraid. It’s a lecture that should be reprinted and posted to every birding social media site.

Johnson’s work on cultural folklore is an important element in “Half-Bird, Half-Spirit: Owls and the Human Imagination,” the chapter examining how we, humans as a group, have looked at owls as symbols of both darkness and light. In some ways, this is a puzzling chapter. It’s a huge subject, especially when you start looking at owl symbolism as it appears in art. Humans were drawing owls 36,000 years ago, as Ackerman points out! Ackerman interviews Robyn Fleming, a research librarian at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, who is documenting every owl-related artwork in the museum’s halls and storerooms, so far identifying 550 pieces. The tip of the iceberg when it coming to counting every artwork in the world that depicts owls, but a fair representation of the diverse ways artists and artisans have painted, sculpted, etched, and drawn them across countries and cultures.

Johnson’s team has interviewed people about their thoughts and feelings about owls in 26 countries, amassing 6,000 interviews. There is good reason for the interviews, beyond simply amassing information, and this becomes clear in the final chapter, the Afterward, about conservation. Owls are in danger from the usual threats–habitat destruction, climate change, human intrusion. They are also threatened by cultural beliefs that lead to killing them because they’re seen as harbingers of death and bad luck. They are also hunted. People and organizations in Nepal, Zambia, and South Africa have sought to change cultural attitudes, having the most success with school children. Ackerman skirts around a related problem, the trade in owls in markets in southeast Asia and Japan, an outgrowth of Harry Potter mania. It would have been interesting to know more about this gray area–I’m thinking of writer Jon Dunn who poked into South American markets in search of hummingbird artifacts in The Glitter in the Green–but I can see where this is one direction the author would not want to take.

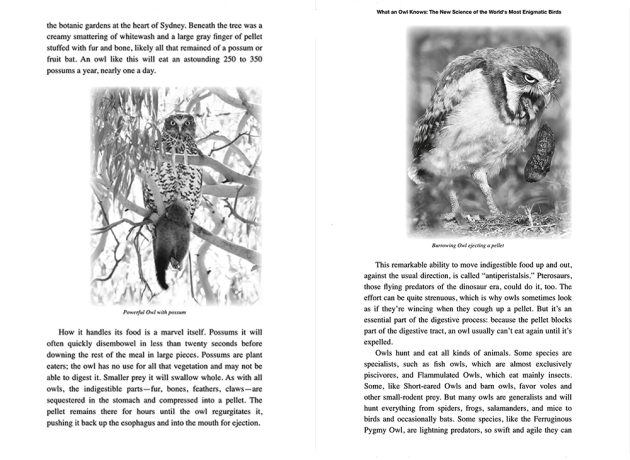

Black-and-white photographs are scattered throughout the book, illustrating stories, research finds, and artwork (see above). If any bird lends itself to the beauty of black-and-white photographs, it’s owls, but I’m happy there is also an eight-page color insert displaying 23 photographs of live owls and artwork owls. Color helps show the subtle gorgeous variabilities of different species’ gray-brown-black-white plumage (particularly notable in a page featuring side-by-side portraits of four totally different species by Brad Wilson, a professional photographer who specializes in dramatic animal portraits) and gives an immediacy to action shots. Photo credits are given in the back of the book; photographers include researchers interviewed in the book as well as birder photographers and professional photographers from around the world– Matt, Poole, Jeff Grotte, Ceda Vuckovic (who 10,000 Birds readers might know from Dragan’s posts), Melissa Groo, There are some stunning images here and Ackerman thanks them graciously in her Acknowledgements.

The “Further Reading” chapter lists, chapter-by-chapter, books and articles–scholarly and popular, mostly scholarly–that I assume were Ackerman’s sources of information. The citations are impeccable aside from a practice of listing first name initials before the surname. I just wish there was some kind of footnoting or other indication in the text to help the reader go from fact to source. If you didn’t carefully read the table of contents or browse through the book (which you can’t easily if you’re reading a digital version), you wouldn’t even know these sources were there till you were finished with the text, and then you’d have to go back and try to match the fact or theory with the source. It’s a lot of work. I also would have liked more information about where to find some of the resources described in the text but not listed in “Further Reading,” for example, the “interactive web presentation of vocal individuality in owl species” developed by ecologist Pavel Linhart and his colleagues (p. 95). It sounds like fun, but I can’t find it anywhere. The Index, the other essential back-of-the-book section, is very well done and useful once you realize that owls are listed by their whole common name (i.e., ‘Powerful Owl’ is under P). Most of the people interviewed and quoted are listed, illustrations are indicated in italics, and cross-references are smartly employed.

Jennifer Ackerman is one of my favorite bird authors. Her previous books include The Bird Way: A New Look at How Bird Talk, Work, Play, Parent, and Think (Penguin, 2020), The Genius of Birds (Penguin, 2016), and Birds by the Shore (Penguin Press, 2019; originally published in 1995 as Notes from the Shore by Viking Penguin); she’s written many articles and essays, and can be heard on NPR, the ABA Podcast, and, I’m sure, others. In addition to telling stories, she brilliantly evokes sense of place and immediacy of experience. Here is a favorite paragraph from a field trip to a forested mountain north of Charlo, Montana in the company of an ORI team:

This is beautiful Great Gray territory. On the forest floor are small shrubs of snowberry and Mountain Spray, bright patches of spring beauty, and Sagebrush Buttercup. Lichens known as Old-Man’s Beard droop from the pines. Sprigs of Wolf Lichen spring from the Douglas firs, a gorgeous, almost iridescent lime green. Wolf Lichen is rich in toxic vulpinic acid and in the old days was boiled up with meat and used to poison wolves. Though it’s dry terrain and hunting might be hard here, there are good nesting sites, cool and shady, with some impressive snags rising thirty or forty feet, with bowls large enough to accommodate the massive belly of a brooding female Great Gray. Le Fay [an ORI intern] circles them to spot feathers or pellets. (p. 137)

Though a writer by education and experience, she is knowledgeable about the scientific process and excels at interpreting scientific finding to the popular audience through a combination of on-site visits, interviews, and background research. The former must have been difficult for this book; conceived during the pandemic, Ackerman still managed to visit wildlife centers, banding stations, and field stations in the United States, South American, and Europe. I’m wondering if the subject of this book itself presented a challenge. Unlike some of her previous subjects–Ravens, Kea Parrots, Satin Bowerbirds–owls don’t do much. They roost and hunt, at night (mostly) when we can’t see them. I’m impressed but not surprised that Ackerman was able to scratch the surface of the maybe wise, always inscrutable face of the owls of the Barn Owl and Owl families and find riches of behavioral diversity and intelligence. This is a great summer read. It is also a book that will inform and elevate one’s encounters with owls, by design or by happenstance, and make you think carefully about how we, as humans, interact with them.

What an Owl Knows: The New Science of the World’s Most Enigmatic Birds

by Jennifer Ackerman

Penguin Press, June 2023

352 pages; illus.

ISBN-10:0593298888; ISBN-13:978-0593298886

$30.00 (discounts from the usual suspects)

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Most enlightening for this South African owl lover thank you.!