The documentary film The Central Park Effect premiered a little over ten years ago, showing the world that it’s possible to find avian magic in one of the largest, building-dense cities in the world. The film made ‘stars’ of local birders, a diverse cast ranging from the young, the purple-haired, the older, birders lugging big lenses, birders coping with breast cancer, and one black man. Christian Cooper comes on screen about two-and-a-half minutes into The Central Park Effect, appreciating a Prothonotary Warbler at ‘the Point’ while telephoning a friend with the news (this is pre-text group), a nice hint of the collegial networks that underlie Central Park birding. He appears again a few minutes later, seeking out a canopy high Blackburnian Warbler and articulating his Seven Pleasures of Birding, a charismatic presence whose overwhelming joy in birding is contagious even when interpreted through film.

Eight years later, Christian Cooper birding Central Park became a very different kind of media image: the black man falsely accused by a white woman of threatening her life after asking her to leash her dog in the Ramble, an area where unleashed dogs are not allowed. It was the same day George Floyd was killed. I remember that day. I read Chris’s story and saw his video a couple of hours after his sister made it public on social media (I had been Facebook friends with Chris for several years, though I had never met him face-to-face). I was concerned and horrified that this happened in my city and astonished when this seemingly local story became national then international news. Chris Cooper was (and still is) a well-known, valued member of the New York City birding community, a member of the board of directors of NYC Audubon and at the time one of the few black faces seen with binoculars in the Ramble. I knew he was also a former Marvel comic book writer and editor, but did not know that he also, unsurprisingly, had a history of involvement in LGBTQ and Black rights advocacy. Christian spoke eloquently to the criminal justice authorities and the media about the incident, declining to support punishment of his accuser (who had already lost her job and temporarily her dog) and using the incident instead as a platform for opening our eyes to the realities of racism, institutional and personal, and the experience of being a black gay man. And, as he did a decade ago, the joys and benefits of birding.

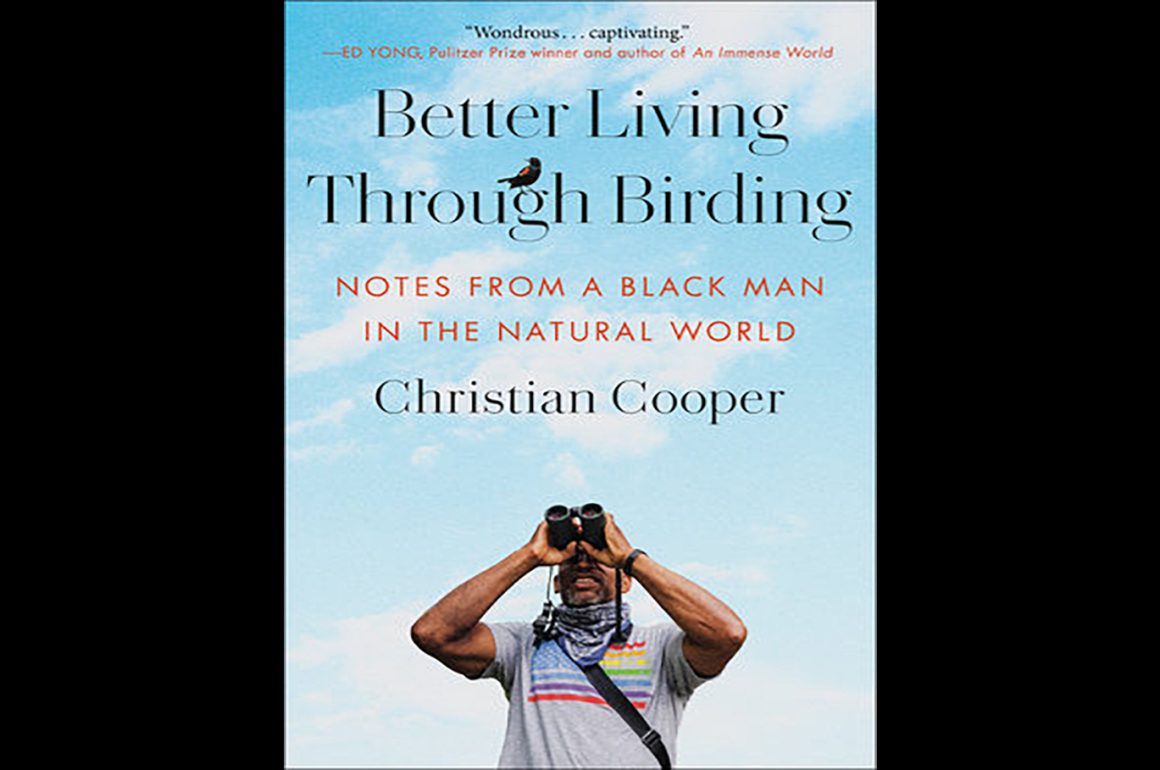

Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World is Christian Cooper’s story. It is not what I expected, totally. It is a skillfully, beautifully written book about finding joy and spirituality in nature and birds. Chris’s recent New York Times article, “Three Years After a Fateful Day in Central Park, Birding Continues to Change My Life,” adapted from this book, encapsulates that essence. It is also about Chris’s personal history: his boyhood in suburban Long Island, college years at Harvard and the struggle to come out, ‘nerdy’ passions beyond birding–namely science fiction books and films, career highs at Marvel Comics, travels to foreign countries, and his complicated relationships with his parents. In other words, we’re getting the whole Christian Cooper, and I’m glad. Memoirs are rare in the birding world. The closest we get are Big Year books which are, with a few exceptions, records of birding, not well-written explorations of one’s life. In Better Living Through Birding, Chris tells us stories of his life, a very unique life, but he also crafts his experiences so we can relate to them as birders and as people. Raw honesty is felt throughout. This is what makes this memoir more than a collection of anecdotes; it’s our opportunity to understand the different parts that make the whole of a black gay man negotiating the natural world and the more challenging, the adjacent “real” world. It’s a book we all should read.

Chris smartly starts Better Living Through Birding with a birding adventure in Central Park. I think talking about it any further would be a spoiler, so I’m just going to say that it’s the perfect entry point, echoing his appearance in The Central Park Effect. He starts listing his “Seven Pleasures of Birding,” ironically with the seventh one, The Unicorn Effect, and explaining to us, the audience that gets it and the audience that needs to know, why birders love birds and why he in particular has needed birds and birding throughout his life:

We have feathered dreams, dreams that have filled my head from earliest youth. Birding served as a refuge as I struggled with being a queer kid in an unwelcoming world, and it simultaneously compounded my Black outsider status while setting my complete and utter nerdiness in immutable concrete. Birding had put me on the path to this once-in-a-lifetime sighting and it would lead me, years later, to another life-changing incident in Central Park, on a day that would reverberate through a nation’s conscience. But before that, it was these feathered dreams that would carry me across the globe on adventures, in search of birds in faraway places. (p. 10)

The next twelve chapters take us through meaningful episodes in Chris’s life, obviously chosen with care, balancing the emotions of the past with the retrospective emotions and analysis of the present, interspersing memories with brief birding stories, birding tips, and the Pleasures of Birding even when the chapter’s topic is not primarily birding. Because being a birder means you experience life through that framework. Graphic bars of a songbird on a branch separates sections within chapters and a graphic of two songbirds on a branch decorate the first page of each chapter, reminding us that even when discussing the politics of a comic book office, birding is a defining parameter. A description of the parenting habits of Emperor Penguins begins the lengthy chapter, “Family Matters,” about Chris’s difficult, intense relationship with his father. A trip to Nepal with a non-birding boyfriend, with the goal of climbing the Himalaya to the foot of Mt. Everest, becomes a torturous exercise in exploring one’s personal mythology and spirituality while maintaining this relationship (and includes this Birding Tip: “Avoid trying to bird in the presence of non-birders…” (p. 175)). Watching the film 12 Years a Slave becomes heartbreaking when Chris hears a Blackburnian Warbler–one of his favorite songbirds, drawn on the inside cover of this book–in the background of a horrifying scene.

For me, an early reader of The Uncanny X-Men, Chris’s chapters on working at Marvel Comics (“Knocking Down Doors in the House of Ideas” and the last section of “Life Turned Upside Down,” a chapter mostly about a pilgrimage to the Australian Outback) are amongst the book highlights. Chris worked two stints at Marvel. In the first, as an editor/writer learning on the job, he became Marvel’s first openly gay editor. He edited Alpha Flight #106, the issue in which Northstar, Marvel’s first openly gay character, comes out of the closet, leading to a media firestorm and intra-company backlash, and created what may be Marvel’s first Lesbian character, Victoria Montesi. In his second stint, he created Star Trek’s first openly gay character, Yoshi Mishima, in the Starfleet Academy comic book series. Chris devotes time to making the Marvel workplace of the early 1990’s come to life–the personalities, the work process, the office politics, the fun. In a way it’s an ironic contrast to his stories about birding, which are largely about birding on his own in Central Park or foreign countries (o.k., he does a couple of trips with his father), with little mention of the workings and politics of the birding organizations in which he’s been active.

The sections on birding are joyous, particularly his memories of learning to bird with the mentorship of Elliott Kuttner of South Shore, and a glorious paean to one day birding Central Park at peak migration in 1989. I read this chapter, “In a Happy Place,” while I myself was birding during migration and totally identified with his description of neglecting everything–laundry, friends, exercise, and for me a book review–because….birds. Other birding stories are more complex, interwoven with memories of Harvard, travel, and re-establishing a close relationship with his father.

And of course, there is the incident in Central Park. The scenario–how it began, what was said, what was videotaped–has been recounted in many newspaper articles, on many television news shows, but it is chilling to read it in Chris’s own words. He frames his story with the murder of Philando Castile, the Minneapolis man shot by the police at a traffic stop while complying with police demands, an act videotaped and live streamed by his girlfriend, and with the racist history of Central Park, created on ground that was once a black and Irish settlement and 132 years later, the site of vicious injustice against the ‘Central Park Five.’ Chris tells his story descriptively and personally, giving dialog and thoughts, including the image of Philando Castile that prompted him to keep recording the encounter “as anyone might whether they were white, Black, brown, Hulk green, or Andorian blue” (p. 247). It’s powerful writing.

Reading this chapter, I thought back to the emotional conversations I, a white Jewish woman, had with birding friends back in May 2020, mostly online (remember, it was still the pandemic). Shockingly, not everybody supported Chris. Some didn’t want to talk about racism and focused on the dog issues. One birder, more acquaintance than friend, became enraged by my and others’ insistence that Chris had been racially threatened and after explosive rants dissolved our social media friendship. No great loss, actually a relief. I wonder if reading Chris’s strongly contextualized, thoughtful recounting of the incident would change this person’s mind. Because knowing what Chris Cooper brought to that encounter–the family history of civil rights activism, the importance of finding a Mourning Warbler, the childhood passion for Star Trek that became a devotion to Vulcan rationality, the consciousness of recent police brutality–transforms it from a news item to nuanced personal history, a human experience. Nah, sadly, probably not.

The final chapter gives some insight into Chris’s life post-Central-Park-incident. His decision to use his new celebrity (he was probably at one point the most well-known birder in North America) to speak for and participate in the issues in which he believes brings him to a place he’s avoided his whole life, the deep South. He’s participating in Alabama Audubon’s first Black Belt Birding Festival, an event that brings him life birds and encounters with black history as he walks through Birmingham and then Selma. As disturbing as these historical echoes are, the trip brings hope and joy; he sees rainbow signs in restaurants welcoming gay people, he meets black birders in the field, he sees a Red-cockaded Woodpecker–a “unicorn,” as his Seventh Pleasure of Birding defines it, a fantasy brought to life–and he ends the day encountering something even more wonderfully unexpected (and I’m not going to tell you what it is because that would be a spoiler). The chapter works well, it brings us beyond the ugliness of the racial incident and into a future that is hopeful in personal and institutional ways, combining all the facets of Christian Cooper’s world.

I have one complaint about Better Living Through Birding: I wish there were photos. I’d like to see photos of Chris birding, his Central Park compadres, his travels, and of his family, about whom he writes with such affection and intensity. And I think the non-birders reading this book would like photos of birds, particularly his spark bird, Red-winged Blackbird, and his beloved Blackburnian Warbler (the drawing is lovely but the bird really needs to be seen in color). We will be getting the next best thing, or maybe a superlative alternative, in Chris Cooper’s newest venture, a National Geographic television series entitled Extraordinary Birder, in which Chris will travel the U.S. exploring birds, their habitats, and conservation. It looks like it will be premiering soon, coinciding with the publication of this book. I’m looking forward to it.

*The Central Park Effect, directed and produced by Jeffrey Kimball, can be viewed on various streaming platforms.

Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World

by Christian Cooper

Random House, 304 pages, June 2023

ISBN-10-0593242386; ISBN-13-978-0593242384

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Thank you for a fantastic book review, Donna, and I can’t wait to read this book!

You’re welcome, Wendy! I hear Chris will be on NPR’s Fresh Air this week.