The Great Egret was in breeding plumage and courtship posture–bright lime green lores, head bending down and then snapping up, long, impossibly delicate plumes waving over its body as if possessed by independent spirits. The visitors along the boardwalk at Wakodahatchee Wetlands, Florida were taking photos nonstop, we only had a few minutes before the wetlands closed, oohing and aaahing. I thought about those plumes and about how fortunate we were to be seeing this egret in all its glory. Plume hunting raged supreme 150 years ago, when egret feathers were part of a worldwide trade in feathers and other bird parts, used for women’s hats and other articles of clothing (but mostly hats), delighting the upper classes and practically wiping out bird species. I could see what all the fuss was about, why they were worth, literally, as much as gold. “Thank goodness for the Migratory Bird Treaty Act,” I said to the photographer beside me, who just looked at me quizzically before returning to her camera.

©2023, Donna L. Schulman

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA) is the legislative implementation of the Migratory Bird Treaty negotiated with Great Britain, on behalf of Canada, in 1916 (subsequent treaties with Mexico, Japan, and Russia have been incorporated into the Act). Its goal was to limit the greedy collecting of birds killed for the plume trade, the bird meat trade (as in the wholesale slaughter of the Passenger Pigeon), and for sport (again, the Passenger Pigeon and declining numbers of waterfowl). It has become the cornerstone of U.S. conservation legislation and regulation, a tool used to protect birds from irresponsible hunting, industrial intrusion and incidental take, habitat loss and pollution, and to encourage best practices by everyone, from birders to corporations. And its passage was not easy.

The MBT and the MBTA were hard-won victories of years of lobbying by concerned naturalists and ornithologists, newly formed Audubon organizations, and a few members of the U.S. Congress and Senate who recognized the need to protect the birds. A number of state laws, with limited and problematic effect, and two major federal laws preceded the MBTA: (1) the Lacey Act of 1900, which made it illegal to transport or sell a bird in one state when illegally hunted in another state, and (2) the Weeks-McLean Act of 1913, which prohibited the spring hunting and marketing of migratory bird and the importation of wild bird feathers for women’s fashion, and which gave the Secretary of Agriculture the power to set hunting seasons nationwide. The Lacey Act still exists, but the Weeks-McLean Act was doomed because it violated the concept, enforced by the courts, that birds belonged to the states, not the federal government. Realizing this, Senator George P. McLean, one of the sponsors of the act, actually more than a sponsor, a true believer, proposed and set in motion the idea of negotiating a treaty (a concept originated by politician Elihu Root). Treaties trump state laws.

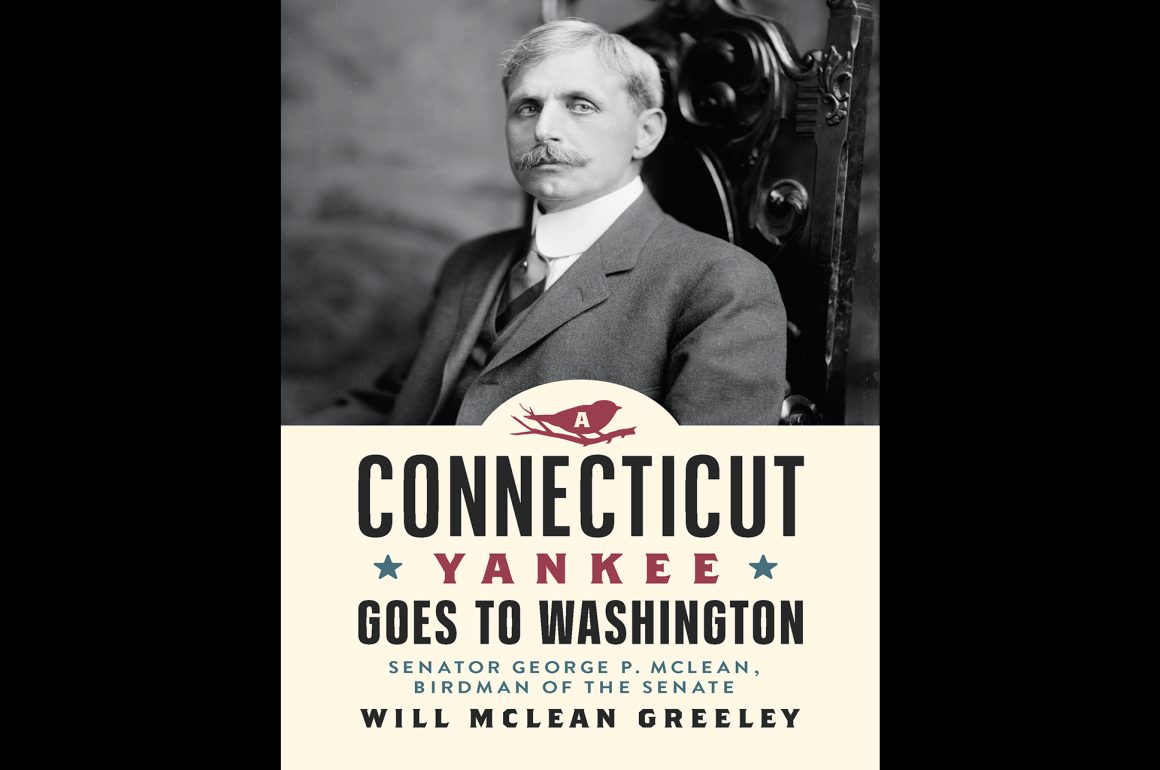

A Connecticut Yankee Goes to Washington: Senator George P. McLean, Birdman of the Senate by Will McLean Greeley is about George P. McLean, the Senator from Connecticut who was determined to save our birds and who used a lifetime of hard-learned political maneuvering, collegial networking, and a worldview focused on the goal, not the glory, to make it work. The biography covers his life from childhood to death (and even pre-childhood, since it reaches back to his Pilgrim/Puritan ancestors), October 7, 1857 – June 6, 1932, and his careers as reporter, lawyer, state governor, and senator. It is set within three significant periods of our history, as Greeley writes: the Gilded Age, the Progressive Era, and the “Roaring Twenties.” (There was also a dip into the Great Depression at the end of his life.) McLean’s work on bird protection legislation is described and analyzed in one 30-page chapter, “Saving the Birds.” You can read just that chapter and the final chapter summarizing this achievement and learn a lot, but it really isn’t the whole story, not the one Greeley wants to present.

A great-great nephew of Senator McLean, Greeley spent three years researching and writing this book. His goal, he says in the Preface, is to fulfill a childhood desire to learn more about a stern figure in a family photograph, a mysterious man with impressive but largely undocumented achievements. But this is not a hagiography. Greeley has a historian’s instincts, perhaps stemming from his training as an archivist (though he ended up, he says vaguely, in business and market research). He has done an enormous amount of research, carefully documented the text, and produced a bibliography 13 pages long. He has consulted unpublished interviews and diaries, government documents, local newspapers, archival collections, and hundreds of books and magazines, mostly on history politics but also on other areas that impacted McLean’s life, like livestock farming. Greeley is not afraid to point out the darker and not very flattering-in-today’s-light aspects of McLean’s life–the depression which marred his last years as Governor of Connecticut, his failure during that tenure to rout out corruption, his later total opposition to women’s suffrage. And although there are times when Greeley tries a little too hard to paint McLean as a man of the people (the story taken from a local newspaper of him talking to a black, elderly caddy on a white Southern golf course really jolts), he succeeds in painting a portrait of a complex, intelligent, modest man of great ambition, a politician who walked a fine line between Progressive and conservative politics, and who learned how to manipulate the system to do good. An excellent writer, Greeley also gives life to many of the chapters of McLean’s life, not an easy thing to do with so little eye-witness material available.

Probably one of the supreme ironies described in A Connecticut Yankee Goes to Washington is that although McLean’s name is attached to the first piece of bird protection legislation, the Weeks-McLean Act, he was not a sponsor of its successor, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. A change of president meant that McLean’s party, the Republicans, were no longer in charge (this is when the Republicans were a different kind of party). The new president, Woodrow Wilson, supported the act, but as a Democrat he put Democratic leaders in charge. McLean, a pragmatist, gracefully accepted the change and, according to Greeley, spent more time than any other Senator making sure the act passed, even when up against the demands of World War I. At one point, Democratic Senator James Reed, his longtime enemy, opposed discussion of the act, saying only war-related issues should be on the Senate floor. Prepared by the Audubon Society with statistics, Greeley was able to link bird protection to crop protection, making it a food conservation priority and thus a war issue. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act was not only a bipartisan legislative triumph, it was a model for legislative advocacy, how nonprofits can successfully work with legislators and politicians.

I think birders will enjoy reading this political history of the MBTA. The conservation side, the story of the egrets and their aigrettes and Frank Chapman counting bird species on the hats of the women of New York City and Harriet Hemenway’s tea meetings becoming Massachusetts Audubon, is fairly well-known (and if you’re not familiar with this history, read Scott Weidensaul’s Of a Feather (2007) or one of the excellent articles appearing on the Audubon and Smithsonian websites). The political and legislative history and the role played by an upper-class, reserved Republican Senator from Connecticut is not. And it should be known. It’s a history that enhances our appreciation for the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, almost gutted under the Trump administration, and also serves as a model, as cited above, of bipartisan cooperation towards a common, mutual good. Is that possible anymore? Maybe. It’s good to have stories that inspire. I do think that only a few birders, those interested in United States history, would enjoy the biography as a whole. This is not a negative criticism, it is a reflection of the audience for this blog. I hope that Chapter 8, the chapter on the MBTA, can be excerpted and reprinted in one of our birding magazines. Or, that birders are able to get A Connecticut Yankee Goes to Washington: Senator George P. McLean, Birdman of the Senate from their local libraries. Chapter 8 is worth the read.

*Note: This review is based on a PDF copy of the book supplied by the author.

A Connecticut Yankee Goes to Washington: George P. McLean, Birdman of the Senate

by Will McLean Greeley

RIT Cary Graphic Arts Press; March 2023)

Paperback, ?350 pages

ISBN-10 : 1939125995; ISBN-13 ? : ? 978-1939125996

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Excellent.