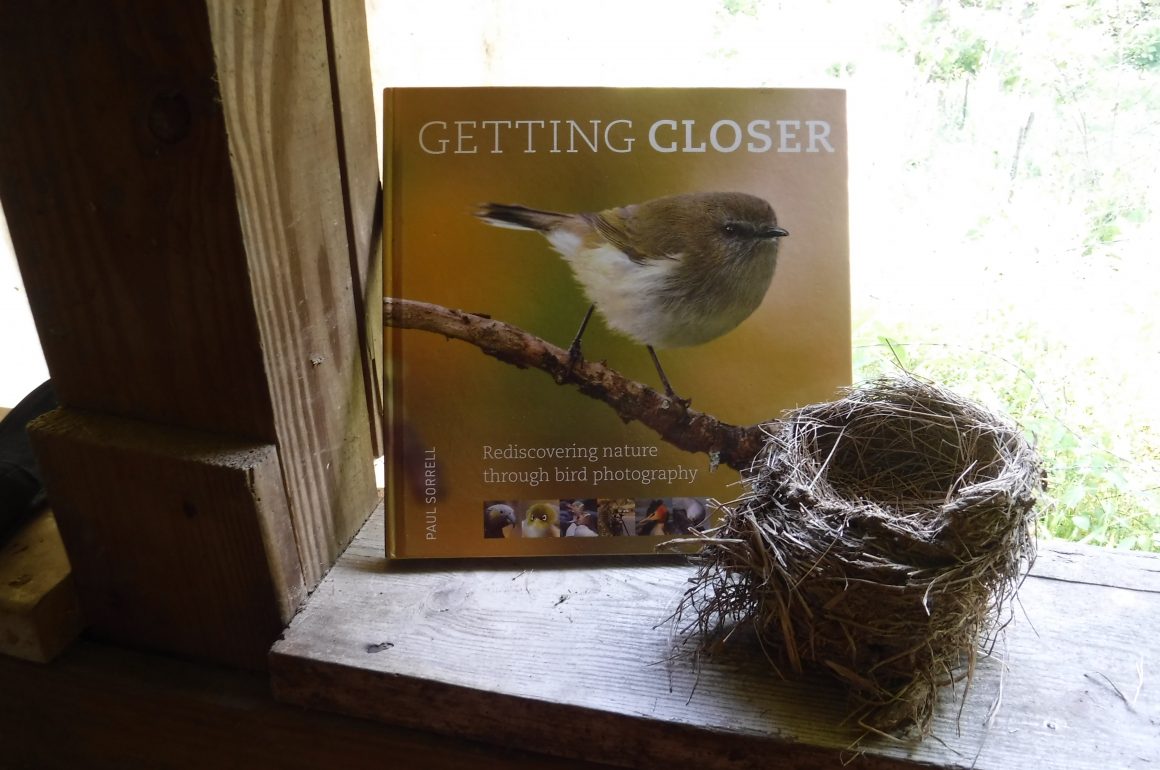

Those birders averse to using the phrase “seriously and irredeemably cute” to describe a wild bird – such people do exist, and are entitled to their linguistic crotchets – may have to change their way of thinking if they see the several photos of the Tomtit in Paul Sorrell’s splendid new book, Getting Closer: Rediscovering nature through bird photography.

He has a special interest in the Tomtit population in the Orokonui Ecosanctuary, near his home on New Zealand’s South Island – but the book includes images of all kinds of Antipodean birds, used to illustrate fieldcraft techniques that, he says, will interest photographers of all levels. His professed goal is to use the template of a photography book to communicate his own love and understanding of the natural world and to inspire others likewise.

Getting Closer is presented in four chapters: “Encountering the outdoors,” “Making the shot,” “The bigger picture,” and “Tools of the trade,” with each of these having multiple subparts of a few pages each. In one titled “Composition 2: Framing Up,” he explains that each of these three Grey Teals strikes a different pose, but the group, closely proximate, can be seen as a single unit; with the focus, going from sharp to blurry, leading the viewer’s eye from right to left:

In the subchapter called “Playing with light,” Sorrell shows how “getting as low to the waterline as possible means that you will capture part of the out-of-focus background as well as the water surface, allowing the subject to ‘pop,'” as this Pied Stilt, doubled by reflection, does:

(That kind of background is called “bokeh,” an effect which a certain ham-handed photographer tried, with limited success, to replicate in the “featured image” at the top of this review.)

And, it must be said, some Kiwi birds are so distinctive, so fetching (on this topic, see Dragan’s rave review of a new guide to the birds of New Zealand) that producing an attractive photo of them would seem (almost) easy, such as this Silvereye:

Obviously Sorrell puts a good deal of thought and attention into his avocation, and there is much to be learned from his book, about natural rhythms, birds in the city, making yourself inconspicuous, color and texture, birds in motion, and many other topics. Some of his specific tips must have been obtained through serendipity, but are delightful to know about. A bird that sees a human walk into a bird blind, he says, may become wary and stay away. But birds are not that good at counting: if two birders walk into the blind, and one then leaves, that “fools them every time!”

(It would be fair to point out, here, that Paul Lewis posted two very good guides, also with excellent practical advice, in this blogspace, earlier this year — “A Slacker’s Guide to Bird Photography (Part One)” and Part Two.)

Sorrell, he makes clear, wants to do more than to simply pass on tips on photography. The state of the world, and dangers to all creatures, including humans, are the subject of his good written Introduction, and they also inform the book as a whole. For humans, “reconnection with nature is our most urgent task” for multiple reasons, not least being the malign, and demonstrable, effects of “nature-deficit disorder” on childrens’ mental and physical health. The goal of his book is, in part, to get people to go outside, and “to reflect on what it means to encounter, appreciate, and record the natural world, especially of course the birds.”

And Sorrell meets his goals: the book, well thought-out and well-presented, is more than the sum of its parts.

(Above: female Tomtit, just as seriously and irredeemably cute as the male; another apt adjective for the Tomtit of either sex, as Duncan points out here, would be “adorable.” )

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Getting Closer: Rediscovering nature through bird photography. By Paul Sorrell. Exisle Publishing, Chatswood, Australia and Dunedin, New Zealand. 137 pp., UK £19.99, US $27.99, CAN $37.99. ISBN 978-1-925820-63-8.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Leave a Comment