Perhaps you don’t know it yet, but with more than 1000 bird species, palm-fringed sandy beaches, developed tourism infrastructure, moderate prices and political stability, Thailand is a country you definitively want to visit. Add to that picture the fact that it offers possibly the best cross-section of Asian habitats and birds available and it becomes a country you need to visit. From lowland forests of the peninsula to the Sino-Himalayan mountains in the north, and from pheasants and hornbills to broadbills and pittas, some 400 to 450 species are possible in three weeks.

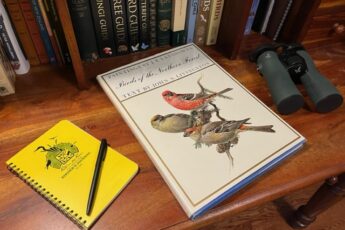

And what do you need to pack? Binoculars and a field guide, perhaps a scope and anti-leech hiking socks too. Everything else is secondary. Or tertiary. Or who cares. Now, which field guide to pack? Since Craig Robson’s “Birds of Thailand” (2002) is taxonomically outdated, the choice was Robson’s “Birds of South-East Asia” (the updated second, 2014 edition of the 2001 classic). Yet, by its very concept – main text tucked in the back of the book, no maps but textual descriptions of bird ranges – this book belongs to another era and the time was ripe for the new field guide.

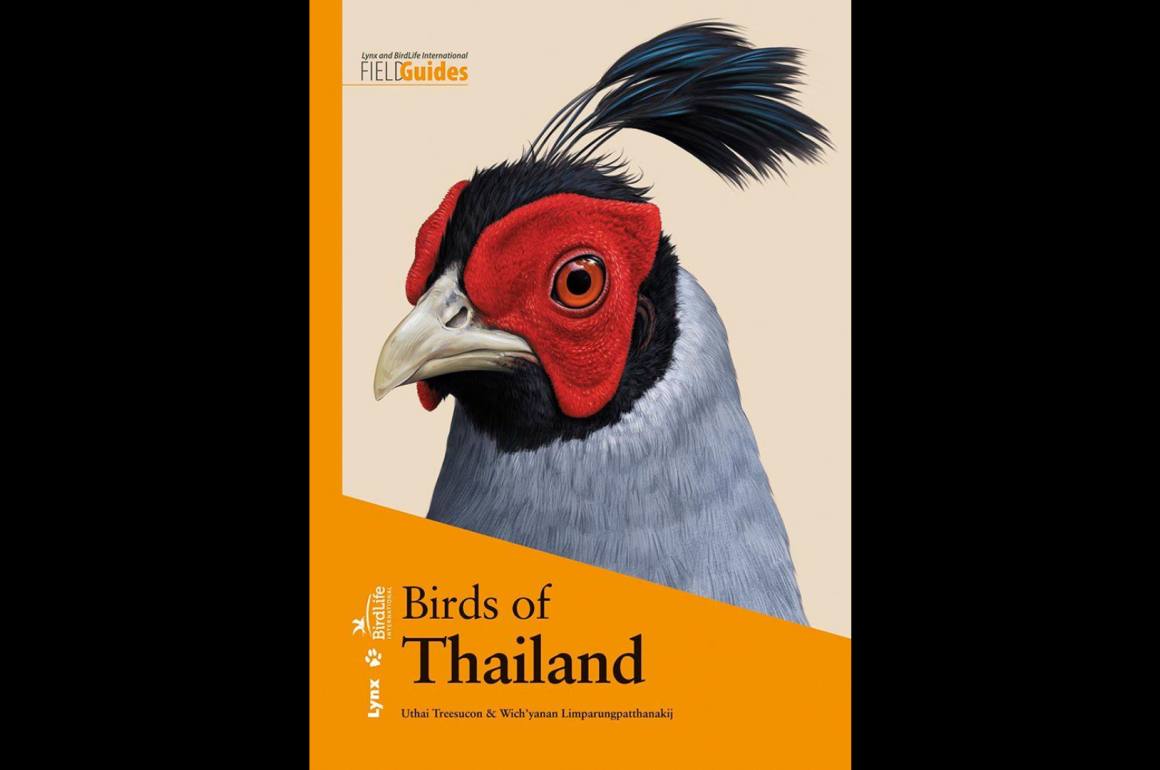

This opportunity was recognized and seized by the Spanish publisher Lynx Edicions, best known for its “Handbook of the Birds of the World” series, which in collaboration with BirdLife International published the latest “Birds of Thailand” (2018). The book was written by Thai authors Uthai Treesucon and Wich’yanan Limparungpatthanakij and illustrated by 30 different artists.

Uthai, a former chairman of the Bird Conservation Society of Thailand, has a Master’s Degree in Environmental Biology and has led birding tours from 1983. Wich’yanan graduated with a Master’s Degree in Biology and has been involved in a number of ornithological research projects in Thailand, as well as being a freelance guide.

With some updates based on subsequent research, their “Birds of Thailand” taxonomically follows the “HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World”. Oh, the taxonomy… As Vincent van der Spek noticed at dutchbirding.nl, two former endemics are no more: the Siamese Partridge is now a subspecies of Chestnut-headed, while the Deignan’s Babbler is considered invalid/conspecific with nominate ssp. of Rufous-fronted Babbler. Further on, there are new splits (is anyone surprised?) adding new endemics: Turquoise-throated Barbet is split from Blue-throated; while Greyish and Rufous Limestone-babblers are also split, but the latter is now an endemic species as well.

In 2200 illustrations and over 1025 distribution maps, the new “Birds of Thailand” covers 1049 species recorded in the country to date. Among them are 20 endemics and near-endemics, and 58 vagrant species.

Out of 452 pages, a ‘dead weight’ are just 50 pages of rather informative introductory chapters, plus indexes, while the ‘active’ field guide covers 402 pages. With Robson’s “Birds of South-East Asia” guide, I would be tempted to cut the ‘dead weight half’ off, in order to carry only the ‘active half’ of the guide into the field – which is not the case here.

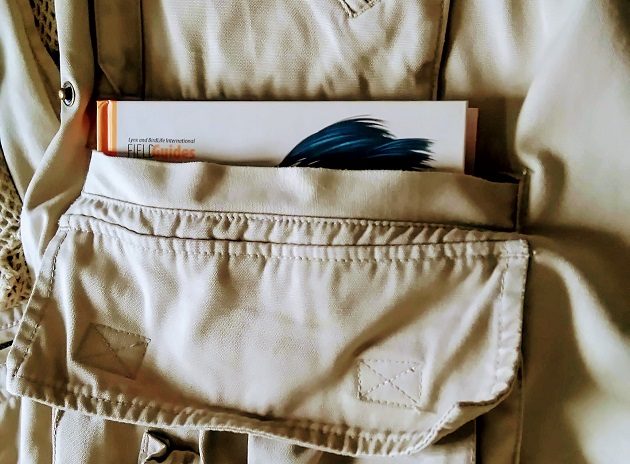

The format is 23 x 16 cm (9 x 6 “) and so far, only hardback is available (personally, I find paperback more forgiving and longer-lasting in field conditions). On my bird guide book-shelf and together with Robson’s “Birds of South-East Asia”, this one is among the largest books, yet, to my surprise, it easily fits the largest pocket of my reporter’s vest. Despite its size, it is not a heavy book. I wasn’t checking the weight, but holding the book in my hand, Robson’s paperback is a bit thicker and way heavier than this new hardback. The Lynx Edicions choose to use a thinner paper – a good choice, I would call it, although it may turn out to be more prone to damage in dump rainforest conditions.

Inner covers hold a physical geography map of Thailand in the front, and the same, this time blank map in the back, with indexed 34 birding hotspots. The introduction covers the geography, climate and for the first-time visitor especially important, habitats: nine forest types, offshore, intertidal, rivers, freshwater wetlands, open country and urban habitats. A brief overview of bird conservation in Thailand follows, together with a list of threatened birds, also listing two data deficient species, the White-faced Plover and the Large-billed Reed-Warbler. The introductory chapters continue with the history of birding in the country followed by another gem: on three and a half pages, not so brief overview of those 34 nature reserves and other hotspots, plus that hotspot map that is replicated here as well. In the back of the book are three indexes, scientific and English names, Thai bird names and bird groups listed alphabetically. The font may be small, yet that is already the standard in field guides and I gave up complaining, but started to wear glasses.

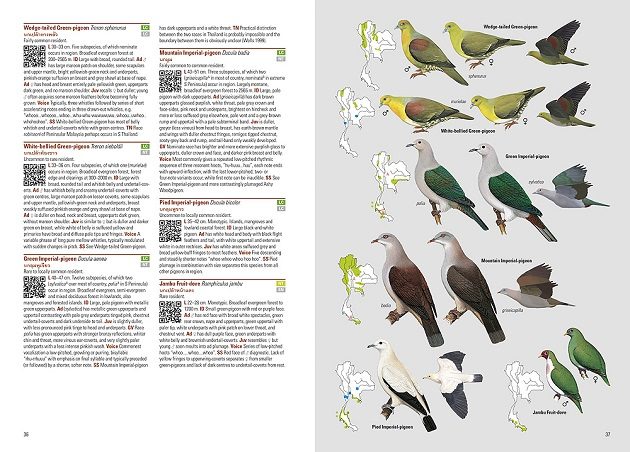

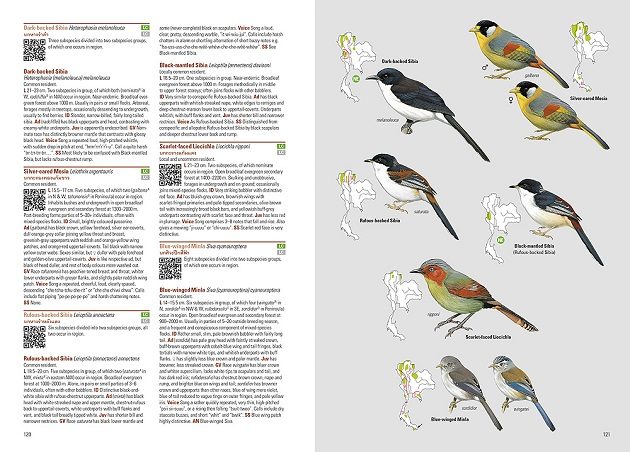

The bird ID text starts with the species name in English, scientific name and the Thai name (I especially respect the addition of this last one), its conservation and occurrence status, subspecies, size, habitat and behaviour, description (sexes, breeding vs. non-breeding plumages and age groups visibly separated by bold red lettering), voice, similar species and alternative names, sometimes followed with taxonomical notes (on, mostly, lumps, splits and possible splits). Reading the descriptions for several species I am particularly familiar with, I find them readable, simple (without being oversimplified) and understandable.

Next to species texts is a novelty I never saw in a field guide before – the QR barcode, a mobile phone readable optical label that in this case links to a relevant Internet Bird Collection website (www.hbw.com/ibc) page, with complementary audiovisual material (dozens of photos, videos and sounds) of the species in question. It works great at home, but overseas you probably need a local SIM card to be able to use it without extra roaming charge (I wonder if there is a phone signal in Thai rainforests, but afterwards, a hotel/lodge should have a Wi-Fi).

The second novelty is the Thailand checklist card that you get with each copy of the book, with a Lynx Edicions website page link and your personal code to download the .pdf checklist that follows the same taxonomy as your field guide (and you would not want it any other way). Besides the usual checkboxes to tick your sightings, it offers the additional info which hotspots to search for the target species. The hotspots are numbered and up to 14 numbers follows the species name, with the best hotspots for the species in question marked in orange, to stand out in the crowd.

The final novelty and a very successful one, is the positioning of range maps. They aren’t at the text page, hence leaving more space for longer descriptions where necessary (which is not too often), but inside the plates, next to bird paintings, so you can quickly check if the species occur in the particular region or not. This unusual idea cannot work with the outlines of USA or Europe, but Thailand has such a narrow and elongated shape that the map nicely fits next to a bird. And for three successful novelties in a single book I really must congratulate the publishers.

Once I read a text about boat building where the author said something like, if you want it to sail well, the hull must look beautiful (or something like that). Whatever the case, it may apply to field guides as well: if you want to ID them easily, the book should look stunning. Despite having 30 illustrators, I do not notice much difference in style, which clearly was the case with Robson’s book (or even with National Geographic Birds of North America). The paintings are, no doubt beautiful, but how successful they are, I can judge only by checking those birds I have a lot of experience with. Which in the case of this field guide turn out to be mostly vagrants.

For example, the White-tailed Eagle. The posture of the standing adult is wrong, in a sense that it is atypical of the species, while the neck and head appear proportionately too small. The birds in flight may be coloured like the White-tailed Eagles, but they do not have the shape nor jizz of this species (too bulging secondaries and too narrow primaries – if I’d see that bird in the wild, I’d say I do not know what it is, but do know what it isn’t, it’s not the White-tailed Eagle). Still, in the Thailand guide, the White-tailed Eagle, a vagrant in the country, is possibly the least important species, and if it’s the only one that is not shown successfully, it doesn’t really matter. You cannot possibly show all 1049 species equally well. So, is it the only one? Going through the book, a great many species and genera I am familiar with do seem convicting, so I will take this eagle as an exemption and not as a rule.

Oddly, not many species are shown in flight. It remains restricted to those groups where absolutely necessary (raptors, gulls, etc.), but e.g. no hornbills or, aside from swallows and martins – not a single songbird. With five to six species per plate, in some cases I am under the impression that the paintings could have been slightly enlarged – or the birds in flight added, to leave less empty space between the species. Strangely, tropicbirds are grey and not white, and egrets are somewhat greyish, too. Also, there are no arrows to indicate the key identifying markings.

In conclusion, a field guide is nothing if not a work of art – and I love the artwork in this one (especially the owls and the hornbills). The text is authoritative and easy to follow. It is not heavy, or at least not heavy for such a large book, but is somewhat cumbersome to carry and being a hardback edition (so far, at least), it doesn’t curve in a vest pocket to follow your hip or bend inside your backpack. (Being a hardback, it doesn’t bend, but breaks.)

Yet, if you already have Robson’s “Birds of South-East Asia” – taxonomy aside, do you need this book? Yes, you do. I already mentioned the position of the main text and the lack of maps in Robson’s, but the final conceptual nail is the lack of bird names in the plates, hence you have to compare the numbers on the right (plates) and the left (a short text) page. The new Treesucon and Limparungpatthanakij’s book (it will probably be known as the Lynx guide) is, simply, more user-friendly and far more comfortable to use in the field. Without doubt – go for it.

Birds of Thailand by Uthai Treesucon & Wich’yanan Limparungpatthanakij, 2018. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN-13: 978-84-16728-09-1. Hardback, 452 pp.

In the end, I remember seeing a Lynx Edicions questionnaire asking their site visitors to vote which field guide should be published next? At that moment I didn’t know what to say and later haven’t found that page, so I haven’t answered. There are only two countries in Africa that are not covered by regional or a country guide, only by the overweight pan-African one: the DR Congo and Zambia. No one is visiting the first and it will remain so for a while at least.

But the second one is reasonably developed, has well known national parks, some famous lodges – you’ve all seen the footage of elephants passing through the reception desk area but had no clue it was in Zambia – and no local field guide. It is not covered in South African guides because they consider it a Central African country and at the time the best option is to take two guides with you: one South African and another covering only those several dozen birds appearing in Zambia but not further south. Which is ridiculous. So, Lynx Edicions, publish Zambia next, you cannot go wrong with it.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Leave a Comment