I was well into adulthood when I took up birding (at least in terms of legal age), and a few more years passed beyond that before I discovered what many birders consider one of the most enjoyable, important – and obsessive – aspects of the hobby: list-keeping. Not long after I first learned of the concept of a life list, I – like I suspect other birders-come-lately have done – began racking my brain for all those unrecorded birds I could remember seeing in those now distant days before I became a birder, in the hopes of padding my personal tally with a few extra ticks.

In the end, my admittedly grasping exercise didn’t amount to much: I couldn’t recall enough details of time or place to justify adding any new species to my list – even if I was sure I saw Brown Pelicans while on vacation somewhere in Florida as a teenager or could remember hearing Eastern Whip-Poor-Wills and Northern Bobwhites while growing up on Long Island. Besides, I hadn’t seen anything all so rare that I wasn’t going to add it to my life list sooner than later (and since have, I’m happy to report).

Except for one species: I have a clear childhood memory of seeing black swans. I still can’t tell you when or where (except that it was definitely in North America – more on that later!) but I do remember being surprised by their ebony plumage and those striking red bills. Even as a kid brought up on reams of fantastical British children’s literature, I knew there was something off about these birds – aren’t swans supposed to be white?

I didn’t know it at the time, but I wasn’t the first person in history to make this assumption: the 2nd-century Roman poet Juvenal famously likened the rarity of a thing to a “rara avis in terris nigroque simillima cygno” (“a rare bird in the lands and very much like a black swan”). In the ensuing centuries, the European notion of the mythological black swan became a popular proverbial stand-in for anything so rare – bird or otherwise – that it defied existence (“as rare as a hen’s tooth” is another one – though that’s since been rendered obsolete, as well).

To paraphrase Henry Ford: in medieval Europe, you could see a swan in any color so long as it is white.

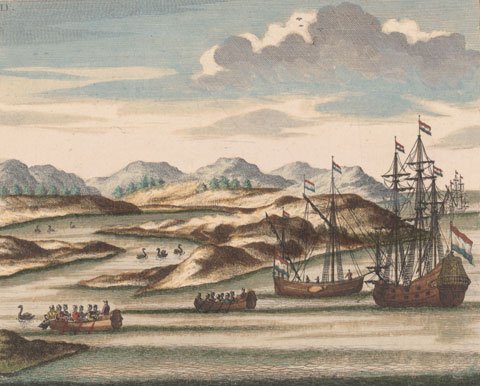

Conventional wisdom upholding the uniformly white coloration of the genus Cygnus persisted for many centuries after Juvenal, until 1697, when the Dutch captain Willem de Vlamingh made a startling discovery in Australia: black swans. The discovery (by Europeans, at least) turned the Juvenal’s long-standing proverb on, well, its proverbial head – a fact noted by early European visitors to the antipodes, including British naval surgeon John White, who wrote in 1790, “We found nine birds, that, whilst swimming, most perfectly resembled the rara avis of the ancients, a black swan.”

A 1726 colored engraving depicting Black Swans and the ships of Dutch captain Willem de Vlamingh at the mouth of the Swan River in Western Australia in 1697 – the first European encounter with this species.

It’s after this species – the Black Swan (Cygnus atratus) – and its unexpected discovery that Lagunitas Brewing Company of Petaluma, California named one of their “OneHitter” series seasonal releases this year. As the label explains, the name was directly inspired by these momentous early encounters with Black Swans that overturned centuries of Eurocentric natural history dogma. When compared to one of the most unanticipated events in the history of ornithology, Dark Swan Sour Ale is more modestly iconoclastic, but still strange enough to merit the name: a dry-hopped sour ale fermented with Petite Sirah red wine grapes, yielding a beer-wine hybrid with an unusually dark tint of its own.

Lagunitas certainly isn’t the first brewery to marry grain to grape: the Belgian brewer Cantillon has been producing Cantillon Vigneronne, a lambic made with Italian muscat grapes since the 1970s, and surely there are countless unrecorded examples going back centuries. And, while this adventurous trend has become more popular in recent years – with brewers and vintners freely borrowing ingredients and techniques from the other camp – the results are still novel and sometimes surprising.

Dark Swan is also noteworthy in being one of the few beer-wine hybrids I’ve seen that uses red wine grapes, instead of grape must or white wine varieties that visually blend more easily with the paler palette of most beers. But there’s no hiding the presence of red wine grapes in Dark Swan: the Petite Sirah grapes used by Lagunitas stain this beer a rich, dark purple, like spilled vino on a white tablecloth. Dark Swan is a dark, ruby beer that shows off brilliant incarnadine highlights in the glass as beautifully as any red wine, while its gentle carbonation and the tight, foamy head – tinged a lovely pale mauve from the grapes – let us know we’re still drinking a beer. The bouquet is fruity and tart, packed with blueberry, blackcurrant, and Concord grape jelly, with hoppy hints of ruby grapefruit and rosemary over the top, and an earthy, almost briny note. After a bright, limy start, the palate is appealingly vinous with jammy touches of plum and pomegranate, followed by a gently sour, almost metallic tinge of green apple candy in the finish. If it weren’t for its telltale purple hue, you could be forgiven for mistaking Dark Swan, with its marriage of sour and bitter citrus flavors, for a blood orange mimosa. This one would be perfect for brunch, of course, or for a refreshing nightcap while enjoying the late, midsummer sunset.

Oh – and as for those Black Swans I saw somewhere, sometime, long ago? They turned out not to be a new lifer for me after all, but instead my first remembered experience getting excited over with an escaped exotic. Easy come, easy go.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Lagunitas Brewing Company: Dark Swan Sour Ale

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Four out of five feathers (Excellent).

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Leave a Comment